SISA'S VENGEANCE: Celebrating JOSE RIZAL'S 150 Birthday Anniversary

SISA’S VENGEANCE:

RIZAL & THE MOTHER OF ALL INSURGENCIES

By E. SAN JUAN, Jr.

Liberty is a woman who grants her favors only to the brave. Enslaved peoples have to sufffer much to win her, and those who abuse her lose her….Les femmes de mon pays me plaisent beaucoup, je ne mk’en sois la cause, mais je trouve chez-elles un je ne sois quoi qui me charme et me fait rever [The women of my country please me very much. I do not know why, but I find in them I know not what charms me and makes me dream.]

--Jose Rizal, Epistolario Rizalino; Diary, Madrid, 32 March 1884

Religious misery is at once the expression of real misery and a protest against that real misery. Religion is the sign of the hard-pressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, the spirit of unspiritual conditions. It is the opium of the people…. After the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be criticized in theory and revolutionized in practice.

–Karl Marx,” Introduction to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” (1843)

and “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845)

In the now classic treatise, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1844; 1891), Frederick Engels formulated the cardinal insight that the inequality of the sexes coincided with the rise of class society: “The overthrow of mother right was the world-historical defeat of the female sex” (1972, 120). Within the patriarchal monogamous family based on private property (land, domesticated animals, slaves), Engels adds, “the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude; she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children.” Women were relegated to the private sphere of the kitchen and boudoir under male authority. Historically, the form of the patriarchal state is a result of the class contradictions prevailing at a particular stage of social development, from savagery to slave, feudal and capitalist stages. The anthropologist Robert Briffault noted that with the institutionalization of monogamous marriage and the nuclear family as the chief economic unit, the supremacy of the male became normative; the male head of household production with property-holding rights and the privilege of disposing of surplus wealth displaced the female in the care of domestic arts and agriculture. Chiefly responsible for the tightly woven communal relationships, women lost their equal share in productive tasks and with it that source of solidarity gutted by “the rise of competitive interests,” by commodity fetishism and the cash-nexus (Hays 1958, 179-80; Caudwell 1971). The fate of Maria Clara at the end of the Noli encapsulates the loss of status of women of the emerging principalia, and of the more intense pacification of her lesser sisters in the symbolic-ideological template of colonial society.

Within this historical-materialist framework, we can properly appreciate Rizal’s works as articulations of a synthesizing theoretical inquiry in which the form of universality springs from the concrete singularity of particular lifeworlds (Oizerman 1981). Aesthetically, they render typical what are specific and individual. The predicament of Maria Clara, Sisa, Salome, Juli, Dona Consolacion and other characters in Rizal’s novels becomes emblematic of the decaying colonial order of nineteenth-century Philippines. In depicting the physiognomies and symptomatic acts of his female protagonists, Rizal also presented a lucid anatomy of the body politic, the diseased corpus for which he was imploring his audience to suggest a cure. In short, the key to understanding Rizal’s revolutionary critique of colonial society may be found in his realistic-allegorical delineation of women in his fiction and discourse. By symbolic extrapolation, Rizal shows how patriarchal supremacy founded on the control of women’s bodies and their productivity becomes the ultimate “weak link” in the colonial class/race hierarchy the toxic vestiges of which still afflict us today (epitomized by the Catholic Bishops’ opposition to the Comprehensive Reproductive Rights Bill (HB 4244) being proposed in the Philippine Congress).

Orthodox/Heterodox Enunciations

In a much anthologized essay “The Filipino Woman” (1952) written at the height of the Cold War, Carmen Guerrero Nakpil elaborated a notion of the Filipino woman as a heterogeneous, multifaceted, amphibious creature that seems to inhabit not those tropical islands in Southeast Asia but some kaleidoscopic realm of fantasy. Not that she defied history or geography; in fact, she dared to encompass both by presenting a hybrid, polychromatic portrait. It is a sophisticated attempt to capture the variegated position of Filipino women in history, offering us a pretext to explore Rizal’s thinking about women, sexuality, gender, and everyday life in the context of anticolonial revolution. If prisons, for Dostoevsky, index the truthful condition of any society, then the situation of women may be considered the revealing veridical symptom of the health or malaise of their habitat, both its sociohistorical and psychic constitution.

Nakpil is a liberal but dilettantish observer of Filipino manners and mentalities. She is careful to discriminate fact from fiction: “Although, historically, it would be inaccurate to go so far as to maintain, as many writers like Rizal and Craig have, that amazonian princesses like Urduja and autocratic matriarchs like Sima once ruled over Filipinos…, these pretty tales of displaced queens seek to symbolize was nonetheless solid and substantial reality.” After the Spaniards converted the Indios and made the Filipina “preoccupied with figleaves,” Rizal and his nineteenth century contemporaries had to go to Europe to get a good look at women.” Rizal’s fictional women were classified legally by the Spanish regimetogether with infants and idiots, Nakpil adds, “for she could neither enter into contracts wihout her husband’s consent, if married, nor leave her home without her parents’ consent before 25, if unmarried.” That applies of course to upper-class women. She concludes that the Filipino woman of the period just after World War II is “a sort of compromise between the affected little Christian idealist of the Spanish regime, the self-confident go-getter of the American era, and the pagan naturalist of her Asiatic ancestors” (1980, 14). From this mixture of lifestyles and essentialized ingredients, Nakpil supposes that in a few generations, the Filipino woman will iron out her “mongrel contradictions” into a ‘thoroughbred homogeneity” embodied in a “clear, pure, internally calm, symmetrical personality.” But she resists such a possibility. Why? Because then she “will have lost the infinite unexpectedness, the abrupt contrariness, the plural unpredictability which now make her both so womanly and so Filipino” (1980,18).

We thus confront a creature both womanly and Filipino despite circumstances and contingencies—is this gendered construct real or imagined? In the midst of the rancorous debate over the Reproductive Health Bill, we wonder whether Nakpil’s image of the polymorphously perverse, composite Filipina body is causing all the furor and controversy. Is this unexpected, contrarious, unpredictable group the pretext, topic, occasion or effect of what is happening?

An analogous controversy bedevils the position of women in Rizal’s discourse makes problematic their catalyzing or counter-bewitching resonance in his life (more on witches later). This is not virginal territory to explore. All the Rizal biographies cannot avoid mentioning, if not belaboring, the propaedeutic influence of his mother Tedora Alonso, Leonor Rivera, and Josephine Bracken, not to forget the shadowy Segunda Katigbak and the vibrant Nelly Boustead hovering over the margins of his memoirs. But from this distance in time and space, it is self-indulgent to speculate on the romantic adventures of the hero—unless we intend to package that aura of erotic melodrama for sale to the profit-maximizing mass media. Are we not reeling from a surfeit of these banalities and trivia? For our purpose of doing an experiment in thought/critique about the function of the female/feminine in Rizal’s thought and its reverberations in ideological struggle, this essay will be limited to a focus on one question: Was Rizal (his life and works) a contributor to the maintenance of the patriarchal order or a critic of the effects of the social division of labor in class society, which is the condition of possibility for male supremacy, sexist chauvinism, and the exploitation and oppression of women? Are characters such as Sisa, Maria Clara, Salome and Juli significant for more than their technical efficacy in the realist narrative? What ultimately is the role of Josephine Bracken in the sequence of women-protagonists in Rizal’s life beginning with, say, Segunda Katigbak? What follows are speculative glosses and heuristic reflections, a cognitive mapping of the subject-position of this “Other” whose subliminal tracks were already outlined by Nakpil’s versatile splicing pen.

Syndrome of the Ideal

Most discussions of Rizal’s women usually start with Maria Clara and her counterpart in real life, Leonor Rivera. Let us not tarry with the first whose value as a model was fully assayed first by Salvador P. Lopez in his “Maria Clara—Paragon or Caricature?” in Literature and Society (1940), and put to rest in the groundbreaking critical inventory of Dolores Feria’s “The Insurrecta and the Colegiala” (1968). Of the informed Rizal commentators, only Nick Joaquin seems to be scandalous enough to salvage Maria Clara from the Victorian cesspool. Joaquin urges us to read again Chapter 7, “Idyll in an Azotea,” and pay close attention to the eyes of Maria Clara and Juan Crisostomo Ibarra, for “the question that love poses in a bright or veiled glance cannot be answered by speech” (1988, 11). But the encounter between the two lovers is noisy, as it were, counterpointed by a plethora of ventriloquizing voices, not a conversation but sequential whispers of two solitary persons communing with conscience or spectral presences.

What is curious is that face to face with his beloved, Ibarra invokes the organ of memory where Maria Clara’s image blends with the landscape of his journeys in Europe mixed with local scenery. Remembrance resurrects the past: Your memory “has been my comfort in the solitude of my soul in foreign countries; your memory has negated the effect of the European lotus of forgetfulness, which effaces from the remembrance of our countrymen the hopes and the sorrows of the Motherland.” For the traveling native, the beloved has metamorphosed into “the nymph, the spirit, the poetic incarnation of my country: lovely, simple, amiable, full of candor, daughter of the Philippines, of this beautiful country which unites with the great virtues of Mother Spain the lovely qualities of a young nation” (2004, 58). Idealization sanitizes the submerged furies of envy and jealousy Amidst this elaborate rhetoric of denying that he has forgotten her sweetheart, the past returns in the farewell letter he wrote, which she reads to remind him of “pleasant quibbles, alibis of a bad debtor.” The demure, acquiescent paramour revives the admonishing tone of Ibarra’s father, with a message recalling the mother’s death and the father’s impending demise, and the need to sacrifice the present for a “useful tomorrow for you and your country.” This patriarchal command, transmitted through the son’s fiancee, agitates Ibarra and compels this retort: “You have made me forget that I have my duties” to honor the dead. Agreed, Maria Clara was not “a namby-pamby Manang,” as Joaquin chides us; and that her confessor found her a problem girl. Nonetheless, she is only a mediating instrument for Ibarra to satisfy the traditional demands of filial piety and vindicate the honor of the ancestral totems. In the end, she is used by Padre Damaso (her biological father) to humiliate Ibarra by forcing the cuckold Capitan Tiago to marry her to another man, Linares.

Matrilineality soon asserts itself. When Ibarra returns after his escape from the arresting police to see Maria Clara for the last time, he renews his vow by figuratively restoring the power of mother-right: “By my dead mother’s coffin, I swore to make you happy no matter what happened to me. You could break your own pledge, she was not your mother, but I who am her son, I hold her memory sacred and despite a thousand perils, I have come here to fulfill my pledge…” (2004, 532). For her part, Maria Clara reveals the secret of her origin—the friar’s violation of Capitan Tiago’s trust and her mother Pia Alba, the break-up of the illusion of the Indio father’s authority—and her promise not to forget her oath of fidelity. This scene follows Elias’ renunciation of the patriarchal order to uphold the tarnished family honor by refusing to take revenge on Ibarra and allow the unity of all the victims seeking justice to supersede his clan’s particularistic interest. Nonetheless, Maria Clara serves throughout as the seductive screen of the fathers and the dutiful sons.

Witness to Emergencies

By the time Rizal was born in 1861, the predominantly feudal/tributary mode of production was already moribund and an obstacle to further socioeconomic development. Trade and commerce expanded when the country was opened to foreign shipping in 1834-1865, especially after the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 (Arcilla 1991). While the islands for the most part remained tribal and rural under the grip of the rent-collecting frailocracy and its subaltern principalia, land-tilling families such as those of Rizal flourished within the limits of the colonial order. Power was monopolized by the peninsulars in the bureaucracy and military, together with the religious orders. They controlled large estates and appropriated the social wealth (surplus value) produced by the majority population of workers and peasants most of whom were coerced under law (for example, the polo servicios) and reduced to slavish penury. Ruthless pauperization also doomed indigenous folk deprived of access to public lands, animals, craft tools, and so on. Only a tiny minority of Creoles and children of mixed marriages (mestizos of Chinese descent) were allowed to prosper under precarious, serf-like, and often humiliating conditions that eventually drove them to covert and open rebellion. Rizal was one of these children sprung from the conjuncture of contradictory modes of production and reproduction of social relations, a child responding to the sharpening crisis of the battered Spanish empire.

Rizal’s family belonged to the principalia, the town aristocracy. His parents owned a large sumptuous stone house and adjacent property; their wealth derived from cultivating rented land owned by the Dominican Order which later expelled them for refusal to accede to a rental increase and other impositions. Rizal’s mother managed a store and operated a flour-mill and ham press; the parents traced their lineage to merchants and provincial officials with affluent Chinese petty-bourgeois provenance (see Chapters 2-4 in Craig 1913). With a private library of more than 1,000 volumes (the largest in Calamba, Laguna), the Rizals (of eleven children, nine were women) enjoyed a relatively privileged rank among the native gentes or clan establishment. Compared to his muted respect for his father, Rizal esteemed his mother in a more expressive and exuberant way: “My mother is a woman of more than ordinary culture; she knows literature and speaks Spanish better than I. She corrected my poems and gave me good advice when I was studying rhetoric. She is a mathematician and has read many books” (1938, 335).

Later on, in an 1884 letter copied by Leonor Rivera, Rizal’s mother would advise him not to “meddle in things that will distress me,” congratulating him on his graduation: “”I’m thanking our Lord for having bestowed on you an intelligence surpassing that of others” (1993, 159). But she wryly cautions him not to be too wise: “If he gets to know more, the Spaniards will cut off his head.” Confident and proud of his accomplishments at the Ateneo and in Europe, Rizal set the warning aside. No doubt Rizal worshipped his mother; consequently, when she was subjected by Calamba’s gobernadorcillo and guardia civiles to the cruel punishment of walking from Calamba to Santa Cruz, a distance of 50 kilometers, on a charge that was never substantiated, Rizal suffered an incaculably profound trauma. It was a deeply painful wound that disturbed him enough to motivate him to condemn—to quote his rationale for writing his novels—“our culpable and shameful complacence with existing miseries,” and “to wake from slumber the spirit of the Fatherland.” The mother’s ordeal served as the primal scenario of violation, the initiation into the crucible of his life’s pilgrimage.

Rizal was then only eleven years old when his mother was arrested on a malicious charge. She and her brother Jose Alberto, a rich Binan ilustrado, were accused of trying to poison the latter’s wife who abandoned his home and children when the husband was on a business trip in Europe. It was Teodora Alonso, Rizal’s mother, who persuaded the brother to forgive his wife’s infidelity, to no avail; she connived with the Spanish lieutenant of the Guardia Civil to file a case in court accusing her husband and Dona Teodora of trying to kill her. Rizal’s recounting of the disaster (in the Memorias entry from Jan. 1871 to June 1872) does not wholly capture the impact of this disaster on the adolescent’s psyche: “The mayor….treated my mother with contumely, not to say brutality, afterward forcing her to admit what they wanted her to admit, promising that she would be set free and re-united with her children if she said what they wanted her to say….My mother was like all mothers: deceived and terrorized…” (1950, 30). Rizal visited her in prison; she endured the unjust imprisonment for two years and half. With his brother also suspected of complicity with Father Jose Burgos, executed with Gomez and Zamora for sedition, Rizal summed up the effect of the two events: “From then on, while still a child, I lost confidence in friendship and mistrusted my fellowmen.” Leon Maria Guerrero rightly appraised this unbearable tragedy of his mother as the key experience that Rizal could not face except through the anonymous student diary we quoted. He grappled with it through the cathexis of a public grievance, the 1872 martyrdom of the three secular priests which tormented his brother Paciano, “not so agonizing or so personal as his beloved mother’s shame,…shamefully imprisoned, unfairly tried and unjustly condemned” (1969, 17; see Baron-Fernandez 1980, 19-20).

Deciphering Eve’s Stigmata

To resolve the trauma, Rizal invented female characters whose struggles sublimated his mother’s experience. Sisa’s plight may be read as Rizal’s attempt to confront the violation of his mother’s honor by indirection and to redress the grievance. But one apprehends an excess in the narrative, more obsessive than melodramatic, more exorbitant than the rhetorical pity and fear evoked by Aristotelian tragedy. In Chapter 21 of the Noli, the guardia civiles arrest Sisa as “mother of thieves,” blaming her for her children’s actions. The mother is thus made answerable and responsible for her sons, not the delinquent father. Sisa’s walk to the barracks is Rizal’s re-enactment of his mother’s torture, an unforgivable outrage. It was not just an empathetic re-living of the mother’s agony but a mimetic performance of the ordeal. This actualization may be construed as a therapeutic effort to assuage the compulsion to repeat the past:

Seeing herself marching between the two, she felt she could die of shame. It is true no one was in sight, but what about the breeze and the light of day? True modesty sees glances from all sides. She covered her face with her handkerchief and thus, going on blindly, she wept bitterly in humiliation. She was aware of her misery. She knew she had been abandoned by all including her own husband, but until now she had considered herself honorable and respected; until now she had regarded with compassion those women shockingly attired whom the town called the soldiers’ concubines [Dona Consolacion, the alferez’s wife, and Don Alberto’s deviant and vindictive wife would represent this group]. Now it seemed to her that she had descended one level lower than these in the social scale (2004, 166).

Sisa’s intense shame attests to the power of gendered socialization primarily mediated through the family and the church apparatus, as Rizal would argue in his letter to the Malolos women. But Sisa’s sense of honor testifies to an inherent dignity, an impregnable self-respect—qualities he recommends for Filipina women to acquire. Sisa’s torment accelerates when this dweller on the fringes beyond the scope of the church bells’ tolling (measuring the extent of Spanish authority) approaches the town: “she was seized with terror; she looked in anguish around her: vast ricefields, a small irrigation canal, thin trees—there was not a precipice or a boulder in sight against which she could smash herself.” Sisa then becomes suicidal as the urban space engulfs her. Alienated from the urban circuit of money and commodity exchange, she is terrified by the signs of civilization. Inwardly she vows to her son that they will withdraw farther into “the depths of the forest.” When she reminds the soldiers that they have entered the town, Rizal’s discourse becomes abstract, generalized, imposing rhetorical distance: “Her tone could not be defined. It was a lament, reproach, complaint: it was a prayer, pain and grief, condensed into sounds” (167). Inside the barracks: “She was convulsed with bitter sobbing—a dry sobbing that was tearless and without words.” Literary artifice becomes impotent here to transcribe maternal anguish, the music of the pre-Oedipal chora (Kristeva 1986). Sisa now resembles an animal, sensuous practice suspended in defensive pathos.

Before she was released by the alferez who was at loggerheads with the friars, “Sisa passed two hours in a state of semi-imbecility, huddled in a corner, head hidden between her hands, hair disheveled and in disarray.” She was summarily thrown out from the barracks, “almost forced out because she was too stunned to move.” She is a non-entity to the alferez, consigned to the domain of inert objects and beasts.

What happens subsequently is Sisa’s transformation into the voice of Nature, the sentient environment of rural Philippines. Conversely, it is the humanization of the stigmatized territory customarily identified with the cultural ambience of savagery and barbarism, with bandits or tulisanes, with outlaws, pagans and vagrant lunatics. With Sisa, however, Rizal describes the process of dehumanization/naturalization, beginning with her calling for her sons upon arrival at her hut, searching her surroundings: “Her eyes wandered with a sinister expression. They would brighten up now and then with a strange light; then they would darken like the skies during a stormy night. One can almost say that the light of reason was ebbing close to extinction.” She wandered“screaming or howling strange sounds. Her voice had a strange quality unlike the sound produced by human vocal chords.” Rizal deprives her of human language and endows her with the more infinitely varied sounds of the elements. The next day, defying the narrator’s wish that “some kindly angel wing would blot out from her features and memory the ravages of sufffering” and that Mother Providence would intervene during her sleep, “Sisa wandered aimlessly, smiling, singing or talking, communing with all of nature’s creation,” except her fellow humans.

In Rizal’s powerful dramatization, Sisa commands a reservoir of psychic energy not found in the other female protagonists. It is not found in Juli, Cabesang Tales’ daughter, whose labor-power had to be alienated when her father joins the outlaws. As though re-living the traumatic ordeal of Rizal’s mother, the narrative voice describes Juli’s walk to the convent accompanied by Sister Bali. “She thought the whole world was looking at her and pointing a finger at her.” Overwhelmed with terror, she resisted Sister Bali’s urging, “pale, her features contorted. Her look seemed to say that she saw death before her” (335). Frightened by the prospect of her lover Basilio’s exile, with wrath and despair, Juli closed her eyes so as not to see the abyss into which she was going to hurl herself”—the desperate assertion of her freedom, a stoic defiance of woman’s enslavement. One can infer a general rule from this incident. When the family’s patriarch can no longer protect the household with the separation of the worker from the means of production/subsistence, the daughter becomes a prey for the lecherous power in the convent. Pushed to the extreme, Juli preserved her dignity, her chastity, in her lethal escape from that profanation emanating from the sacred house of God’s ministers. This anticipates Maria Clara’s prison of Santa Clara in Intramuros at the close of the Noli from which the only escape is madness or enigmatic silence and disappearance enforced by the carceral discipline of a decadent obscurantist institution.

The Pathos of Excommunicating Truth

In contrast to Juli, Sisa is caught in a severe contradiction: she cannot kill herself because her sons need her. The maternal instinct compels communication with other victims. In the latter part of the Noli, we encounter Sisa again on the eve of the San Diego town festival when Maria Clara and her relatives confront the leper, a blind man “singing of the romance of the fishes…” Art and reality collide. The blind singer allegedly contracted leprosy by taking care of his mother. Rizal dilates on this episode of the leper who, like Sisa, uttered “strange incomprehensible sounds.” When Sisa approached the leper sunk to his knees thanking Maria Clara for the spontaneous gift of her locket, what Rizal calls “a rare spectacle” dramatized here incorporates that germ of a universal principle growing out of the historically specific lifeworld of women in that reactionary milieu. It is the negated principle of woman’s decisive function in reproduction, nurturance, and production of subsistence without which a regime of gender equality is impossible (see Ebert (1996). This particular scene speaks volumes on the themes of justice, equality, egalitarian and participatory democracy, ecumenical peace, and ecological survival whose nuanced ramifications we cannot spell out and analyze here. Notice the multilayered implications of the mad mother exhorting the blind leper to pray for the living on the day of the dead, this gesture of reconciling or suturing incompatibles punctuated by the clamor of the normal spectators to separate the two victims:

As he felt her contact, the leper cried out and jumped up. But the mad woman held on to his arm to the great horror of the bystanders, and said to him: “Let us pray!…pray! Today is the day of the dead! Those lights are the life of men; let us pray for my sons!”

“Separate them, separate them! The mad woman will get contaminated!” the crowd was shouting, but no one dared to approach them.

“Do you see that light from the tower? That is my son Basilio who comes down by a rope! Do you see that one from the convent! That is my son Crispin, but I am not going to see them because the priest is sick and has many coins of gold and the coins got lost. Let us pray, let us pray for the soul of the priest! I brought him amargoso and zarzalidas; my garden was full of flowers, and I had sons. I had a garden, I was taking care of flowers and I had two sons!” (2004, 249-50).

Of the various thematic strands and motifs woven in this network, I will only stress three: 1) the horticultural stage of social production alluded to recalls the stage of the matrilineal/matrilocal setup in primitive society, a time when the communal household enabled the reciprocal division of labor between the sexes—notice the absence of Sisa’s husband, her supervision of the household and her subsistence obtained from working the land (productive labor as one form of praxis); 2) the parasitic excess of a mercantile economy (centered on coinage extracted by friars, thus combining religious ideology and trade/commerce) monopolized by a theocratic state and a frailocracy whose mercenary use of religion demystifies their legitimacy in purveying the mystical and magical; and, finally, 3) the contamination/contagion of an alienated society, misrecognized but actually lived by the people who called for the separation of the physically diseased and the psychically abnormal, both appendages of a cancerous body politic.

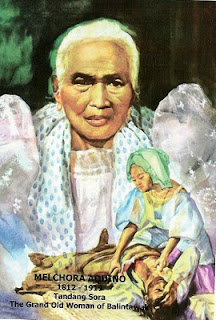

We cannot help but register the behavior of the crowd as cynical, callous and hypocritical. The spectacle manifests a further irony inscribed in the fact that the living have mortgaged their destinies to the dead—indeed, one can say that the dead fathers, tradition, fetishized rituals, idolized metals and commodities (symbolized in the Fili by the hypnotic power of Simoun’s merchandise) have taken over. Aside from taxes and governmental levies on ordinary citizens, the selling of indulgences, and other sacramental fees and tributes collected by the church demonstrates pervasive corruption. In the last chapter taking place on Christmas Eve, Basilio catches up with his deranged mother. Finally she recognizes him and is briefly restored to normalcy, only to die and be consumed in a funeral pyre together with the fugitive Elias. Phoenix-like, Sisa’s motherhood is affirmed only to be dialectically cancelled and preserved or sublated into the predicament of other surrogates and avatars—Melchora Aquino, Salud Algabre, Felipa Culala, Maria Lorena Barros, Cherith Dayrit, Luisa Posa-Dominado, Kemberley Jul Luna, and other militants in the national-democratic insurgency. We still labor under the sharpening crisis of the imperial fathers and their native acolytes, alarmed by the resurgent nationalism of fiery woman-warriors (Aguilar 1998; San Juan 1999).

Exorcising the Two-faced Goliath

We need not linger over the semantic and philosophical complexities of other episodes where Sisa intrudes. Suffice it to mention here the scene in Chapter 40 where Dona Consolacion, the alferez’s crazed wife tortures Sisa; or in other episodes where Sisa’s seemingly gratuitous appearances at the margin of festivities disrupt the quotidian trappings and ceremonies of the respectable. As an antithesis to the maternal archetype (instanced by the negative examples of Maria Clara’s mother, Dona Victorina de Espadana, and others), Dona Consolacion may be interpreted as the wicked half of the ambiguous duality of the mythical pair Demeter/Persephone, the Laura/Flerida duality in Francisco Balagtas’ awit, or Kali, the Indian goddess of fertility and destruction (Eliade 1958, 418-19). Alterity operates within the gender dichotomy, as in all socially constructed identity. Dona Consolacion is a modified specimen of the genre. Isolated and frustrated, forbidden from participating in the festival, “she saturated herself in her own bile,” ready to unleash repressed energies on anyone in sight. We confront again the archaic Furies hounding the perpetrators and apologists of matricide.

Rizal amplifies her Medusa-like malignance in a way complementary to Sisa’s unnnatural look: “Her eyes glittered like a serpent’s, caught and about to be crushed underfoot. They were cold, luminous, piercing, akin to something slimy, filthy and cruel” (346). Is this the sensitive, devout Rizal repulsed by the loathsome aspect of the sinful Eve, the mesmerizing siren and wily temptress of myth and fable? Her unrelenting brutality toward Sisa who was reduced into an animal emitting “howling sounds” can perhaps be understood as a release of dammed-up resentment against her husband; but what enables her to do this is her sharing the alferez’s status evident in her taunt: “Cursed be the mother who gave you birth!” With equal fury, Dona Consolacion attacks her husband, blaming him for not allowing her “to fulfill my duties toward God!” This episode is a hilarious vaudeville of marital conflict and its reverberating tensions, as evinced in the case of Uncle Alberto cited earlier. Rizal satirized local mores and manners with gusto, somewhat diverting us from the real target of the degradation of both sexes; but the power of Rizal’s critique ultimately inhered in the grasp of the totality of social relations, which subsumed the economic structures sutured to the racializing ideology and institutional practices of Spanish colonial power. What is true and real in the lived experiences of Rizal’s characters (as well as his contemporaries) acquire meaning and significance only within the context of the historical totality, in the dynamic sequence of the past moving to the present and future, in nineteenth-century Philippines.

The patriarchal age might be coming to an end, as Rizal once intoned; but its repressive legacy endured up to his death, and after. Dona Consolacion and her benign counterparts, such as Paulita Gomez and Dona Victorina, may be Rizal’s strategy of thwarting feminist protest. After all, not all women conform to the Maria Clara/Leonor Rivera model. Early experiences involving Consuelo Ortigas, Leonor Valenzuela, Segunda Katigbak, the anonymous older L. of an adjacent village, not to mention the unstinting solicitude of his mother and sisters throughout his life, all offered Rizal comfort and affirmation of his virility in one degree or another; none threatened him. So whence the need to invent a nasty violent female protagonist, displaying her irrational fury and then neutralizing her by parody and caricature so as to guarantee our safety from her claims to rational judgment? Why exhibit women’s aggressive capacity, her destructive potential? Why the need to exorcise the derelict, malevolent wife of uncle Alberto—if not to purge the devastating trauma of her mother’s torture?

Unrequited love cannot justify any suspicion of Rizal’s chauvinism. With Segunda Katigbak, it was Rizal’s internal schism that prevailed: “But at the critical moments of my life I have always acted against my heart’s desire, obeying contradictory purposes and powerful doubts” (1950, 52). That crisis occurred in December 1881, six years before his engagement with Leonor Rivera was annulled by her parents who could dispose of their daughter’s body without consulting her. Even though he enjoyed Nelly Boustead’s company, among others, and succumbed to the O-Sei-San’s insidious charm—addressing her in his diary, Rizal confessed that “No woman, like you, has ever loved me. No woman, like you, has ever sacrificed for me,” not even his mother or his fiancee (Zaide 1984, 132), Rizal confessed that he almost grew mad when he lost Leonor. It was the “first sledgehammer blow” of the railway construction that fell on him; the British engineer Kipping was a free man, Rizal was not (1999, 113). What was the lesson? It was not just another male replacing him, it was a burgher-citizen of the imperial metropole trouncing the Indio subaltern from the contest for a conjugal partner. It was industrial capitalism blasting the ethnic walls of empire—only to sustain the patriarchal domination of women’s bodies.

Leonor Rivera died on 28 August 1893. While in exile in Dapitan, Rizal met Josephine Bracken (a Eurasian orphan from Hong Kong, Asia’s burgeoning commercial center) in February 1895 with whom he fell in love. In March 1895, he wrote his mother to extend hospitality to Josephine and treat her as a person “whom I hold in great esteem and regard, and whom I should not like to see exposed and abandoned” (Guerrero 1969, 363). This “errant swallow” promised refuge from a hostile world, but she also functioned as an opportunity to re-affirm his manhood years before the time he could sacrifice his life to the object of his life’s mission: decolonizing patria.

The Shaman’s Strip-tease Agency

Accompanying the estranjera Bracken, the figure of the vindictive wife (of Uncle Alberto and others) returns to the life of the Dapitan exile in the shape of his research into psychosomatic illness. On 15 November 1895, Rizal wrote the “notes for the study of Philippine medicine” entitled “The Treatment of the Bewitched,” purportedly a scientific account of the etiology of a disease not caused by the usual pathogenic factors. What is striking is the description of the female witch, the manggagaway (the mangkukulam, the male counterpart, seems relatively harmless), who inflicts a most mysterious, terrible illness, “though fortunately rare.” The male mendicant magician is but an “involuntarily malevolent fakir,” whereas the female sorcerer applies “diabolical arts” the origin of which is really the social milieu, the cultural prejudices, customs and folkways of the time. Rizal diagnoses this type of sorcery as a result of auto-suggestion accompanying delirium, delirium defined by Rizal as “the lack of equilibrium between the perceptions and the conscience, a civil war inside the brain” (1964,180). This delirium is what afflicted Sisa and Juli in one degree or another. This civil war between what Freud would call the reality-principle and the pleasure-principle, between the warring forces of eros and thanatos in an Oedipalized system, acquires sociohistorical embodiment and performativity.

In Luzon, Rizal informs us that there are towns where all the women enjoy the ascriptive reputation of being a manggagaway—a diagnosis applicable to the entire colonial formation and its psychosomatic dynamics. The cure is immanent in its diagnosis. Here is Rizal with the physician’s objective stance unable to escape pronouncing judgment on the conduct and behavior of the whole society:

Although some deserve the name for their inexplicable vainglory, for their prattling, for believing that thus they make themselves terrible, nevertheless others are absolutely innocent…A certain air, a behavior somewhat reserved and mysterious, a certain way of looking, infrequent attendance at religious services, and others, are enough to win for an unfortunate woman the reputation of manggagaway. She is the she-ass of burden of ignorance and popular malevolence, the scapegoat of divine chastisements, the salvation of the perplexed quacks. Mankind also has divine defects among its divine qualities. It likes to explain everything and wash in another’s blood its own impurities. The woman manggagaway is to the common man and the quack what the resentment of the gods, the demon, the pacts with the devil in the Medieval Age, the plethora of blood, neuroses, and others were to the different ages: She is the diagnosis of inexplicable sufferings (1964, 178).

The witch, more exactly the phenomenon of bewitchment, condenses all the tensions released from the pressures of overlapping conflicts and converging contradictions of a transitional phase in society, that is, a society undergoing revolutionary upheavals. Rizal performs the rite of the exorcising, medical shaman. Instead of inveighing and counter-cursing, Rizal’s tone is elegiac, oracular, trying to discriminate and refrain from distinguishing the guilty and the innocent. Nonetheless, as a scientist-physician, he targets human infirmity in not using reason to analyze and cure the psychic malady. I submit that this discou4rse and its context exemplifies a memorable instance of Rizal’s historical-materialist sensibility and his ethico-political vocation.

In that passage we witness Sisa and Dona Consolacion distilled in one phenomenal figure. What Rizal enunciates, in general, is a hermeneutic of good and evil coexisting together, what is heretical and impious coalescing in one subject-position. Actually, it is a mirror-image of Rizal as the pernicious and treasonous Indio, the unpatriotic expatriate (for the friars) defying the Comision permanente de censura by speaking of the true and the real. The witch is Rizal; but the curse is this counter-statement, the doctor’s report. Alienated colonial society ascribes the source of its vices, crimes and ignorance to a fraction of the female sex and, in this collective process of purification, acquits male authority of any wrongdoing. Impartiality requires settling account with the patriarchs.

Certain sisters of Eve functioned as scapegoat-like Christs, just as the penitent whore Magdalene came about due to “the powerful undertow of misogyny in Christianity, which associates women with the dangers and degradation of the flesh” (Warner 1976, 225; for the communist-oriented views of early Christians regarding women and the family, see Kautsky 1925, 347-354), hence the whore becomes a beloved saint. In Rizal’s polyvocal discourse, the realms of the sacred and profane are two halves of the same coin, one an inquiring mirror of the other; hence, the term “divine” operates here as a symptomatic rubric of the religious illusion, the ideological narcotic, that the Enlightenment and the bourgeois revolutions in Europe had failed to uproot. It is now Rizal’s turn to enlighten his women compatriots, in particular, of the need to liberate themselves from what William Blake called “mind-forged manacles” by their own collective effort and initiative. It is time to re-instate the primacy of personal autonomy and civic solidarity in the arena of everyday life.

The Epistle to the Women of Malolos

Teaching and learning, for Rizal as scholar-researcher in history and ethnology, are indivisibly fused in his role as committed public intellectual (Baron-Fernandez 1980; Ocampo 1998). Study, collective learning, is part of emancipatory praxis which connects human agency and the ecosystem, as Marx implied in his thesis on Feuerbach: “The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionizing practice” (Tucker 1972, 145). His now famous letter to the young women of Malolos, dated Feb. 22, 1889, was elicited by the chief propagandist expatriate, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, while Rizal was preoccupied with annotating Morga’s chronicles in the British Museum in London, and answering the critics of the Noli (Ocampo 1988). It was deliberately written in Tagalog at the time when he was also preparing his first article for the reformist journal La Solidaridad entitled “Los Agricoltores Filipinos.” That intervention may be compared to Karl Marx’s two contributions to the Rheinische Zeitung on the law against thefts of timber and on the destitution of the Moselle Wine Growers (McLellan 1970, 95-101).

In Rizal’s inquiry into the backward conditions of the Filipino farmers, he deplored how the farmer capitalist had to battle not only floods and locusts but also petty tyrannical officials, the constable of the civil guards and the bureaucrats of the court and the provincial government. Already equipped with an astute comprehension of the social relations of production, the political economy of the Spanish colony, Rizal this time focused his critique on the efficacy of the ideological apparatus in sustaining the unrelieved subjugation of the natives, in particular the disciplinary subalternization of women, whom he considered crucial in the formation of children’s personality and disposition. In re-visiting Rizal’s militant propagation of a historical-materialist critique of society through his novels and various discourses, contra Constantino (1970) and vulgar Marxists, we can appreciate his singular contribution to humankind’s revolutionary archive, whatever his other limitations given the circumstances and contingencies of his personal situation and the state of the world in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

The central burden of Rizal’s letter is the critique of religion, more exactly, its practice of idolatry and attendant fanaticism which violate saintliness defined as obedience to “the dictates of reason.” Thus he bewails servitude and “blind submission to any unjust order,” since each person can use a god-given reason and will to distinguish the just from the unjust. Positing the radical premise of all humans being born free, with no right to subjugate the will and spirit of another, Rizal urges the use of reason or rational judgment in all activities—not just in learning Spanish, which for the Malolos women was really a pretext to have access to the guidance of Teodoro Sandiko, Rizal’s progressive compatriot, whom they wanted as teacher (the petition was eventually granted, but Sandiko was replaced by a person approved by the church). What is lamentable, for Rizal, is the Filipino woman’s failure to be good mothers due to their profligate addiction to gambling, their subservience to the mercenary friars, their zealotry in conforming to reified rituals, and their complacent ignorance: “What sons wll she have but acolytes, priest’s servants, or cockfighters?” Sisa’s gambling husband and her two sons in the convent loom in the background. In suggesting that mothers replace the friars as the fountainhead of moral guidance in the family, Rizal valorizes the agency of mothers as educative/formative forces primarily responsible for shaping the character of their children: “…you are the first to influence the consciousness of man…. Awaken and prepare the will of our children towards all that is honorable, judged by proper standards, to all that is sincere and firm of purpose, clear judgment, clear procedure, honesty in act and deed, love for the fellowman and respect for God” (1984, 327). Rizal affirms his faith in the power and good judgment of Filipino women. He believes that Asia is backward because Asian women are ignorant and slavish, whereas in Europe and America “the women are free and well educated and endowed with lucid intellect and a strong will” (128). We know that Rizal admired German women who “are active and somewhat masculine,” not afraid of men, “more concerned with the substance than with appearances” (letter to Trinidad Rizal, 11 March 1886; 1993, 223). The figure of Teodora Alonso, the moralizing mother-teacher, is not far behind.

Excursion to Sparta

It is therefore not surprising that Rizal would invoke the civic conscience of Spartan mothers as exemplary. We should first grasp the truth of our situation, he reminds his Malolos audience, perhaps deducing lessons from his own experience: young students lose their reason when they fall in love, and so beware. Moreover, marriage makes shameless cowards of the bravest youth. Rizal then advises women who are married to “aid her husband, inspire him with courage, share his perils, refrain from causing him worry and sweeeten his moments of affliction… Open your children’s eyes so that they may jealously guard their honor, love their fellowmen and their native land, and do their duty,” like the women of Sparta (1984, 330). Rizal extolled Spartan women for giving birth to men who would willingly sacrifice their lives in defense of their homeland.

But Rizal did not mention how that was possible because of the austere militaristic regimen imposed on the training of youth, the rigorous routine of the agelai or herds (described by Plutarch) in disciplining youth solely for fighting. Ruled by an exclusive ruling caste, Sparta suppressed their serfs with a permanent military organization (a standing army) and a tribal system of common ownership that prevented the disruptive effects of commodity production, industry and trade using coinage.(Thomson 1955, 210-211). The Spartan oligarchy administered the clan settlement (family estates with serfs) as the prime economic unit based on communal ownership of the soil and local handicrafts. Spartan women were also trained in the agelai but “they were free to go about in public; adultery was not punishable or even discreditable; a woman might have several husbands” (Thomson 1968, 190). We are still in a quasi-primitive communal society where women’s work extended beyond the private household. In supervising the production of subsistence and other use-valued goods, they exercised a measure of power in the public sphere.

It is clear that Spartan mothers were not the educators Rizal conceived them to be. They did not raise their sons who, at the age of seven, were enrolled in the agelai and transferred to the Men’s House at nineteen, devoting themselves to military exercises. When married, Spartan men did not live with their wives but visited them clandestinely on occasions; the brides/wives lived with their parents. Women obtained substantial dowries and inherited two-fifths of the land in the absence of their husbands; though excluded from political life, their indispensable position as heiresses and managers of the estates gave them so great an influence that Aristotle spoke of Sparta as a country “ruled by women” (Thomson 1968, 192). Because of the division of labor between the sexes, all adult males served in the standing army while the women administered the family estates. This is what allowed Spartan mothers to sternly judge the performance of their soldier-sons, not their care or nurturance in the private domain of the father-centered home, as Rizal seemed to believe. Education was in the hands of the patriarchal oligarchy of Sparta, not in those of mothers or daughters.

One would expect Rizal to be more knowledgeable or informed, but surely a full- bodied description of Spartan society was not his intention. His purpose was to praise their independence and their selfless devotion to the defense of their homeland. In his 1886 letter to his sister Trinidad, Rizal objected to the Filipino women’s obsession with clothing and finery attuned to the demands of the marriage market. His instructions at the end reiterate the fundamental virtues of courage, diligence, dignity, and personal autonomy derived from acquiring knowledge (“ignorance is servitude”) and the cultivation of intellect, as well as the fulfillment of reciprocal obligations toward others. This repeated exhortation to cooperation and mutual help, a pre-requisite in forging national sentiment (Majul 1961, 73-185), precedes the somewhat peremptory fifth injunction: “If the Filipina will not change her mode of being, let her rear no more children, let her merely give birth to them. She must cease to be the mistress of the home, otherwise she will unconsciously betray husband, child, native land, and all.” Beware, parents of Leonor Rivera, Segunda Katigbak, and their sisters—you may be nurturing treacherous wives who pretend to be “mistress of the home” while scheming to deliver husbands, children, homeland, to the enemy. Rizal’s parting words seem even more rebarbative: “...may you in the garden of learning gather not bitter but choice fruit, looking well before you eat because on the surface of the globe all is deceit and the enemy sow seeds in your seedling plot.”

In spite of such shortcomings, the sixth instruction in Rizal’s epistle sums up his pedagogy: to value intelligence and reason as the principle of equality and solidarity with others. What is reasonable and just is the aim of learning; “to make use of reason in all things” entails the rejection of egotism and the local barbarism of folklore, superstitions, fossilized notions, and anachronistic habits that prevent Filipinos, men and women, from reflecting on their common situation and critically analyzing the impact of movement and change in their collective life. One can apprehend in Rizal’s emphasis on using the “sieve of reason” mobilized to grasp “the truth of the situation” an over-riding insistence in developing civic consciousness in women, expressed here as praise for their “power and good judgment,” “fortitude of mind and loftiness of purpose,” and so on.

Anxious to defend women’s honor maligned by the friars and abusive Spanish visitors, Rizal can only retort that Spanish women themselves are not all “cut after the pattern of the Holy Virgin Mary.” Since the Malolos women for the most part belonged to the ilustrado/principalia class comprised of monogamous families with bilateral extensions, Rizal can only abstractly valorise rationality as distilled in the concrete practice of nurturing children. The everyday life becomes a domain of paramount concern. In the process, he appraises women’s work in the household as one mediating the relations of the natural and social orders. This domestic work creates what Antonio Gramsci calls “the first elements of an intuition of the world free from all magic and superstition (1978, 52). Learning, education as the internalized absorption of modalities of empirical investigation and synthetic-analytic reflection, follows Rizal’s insight (written from Barcelona circa 1881) that “the knowledge of a thing prepares for its control. Knowledge is power” (1999, 70).

Unlike Sisa, Juli, Salome and women of the peasantry and village artisans, the Malolos young women—Rizal surmises—are struggling to overcome the bondage of limited schooling and constricted participation in civic affairs due mainly to the consensual routine of stultifying religious indoctrination. In addition, one has to reckon with paternal authoritarianism and the long tradition of the pasyon and its focus on the mystical transcendence of human suffering. The petition submitted to Gov. Valeriano Weyler to open a night school so that young women might learn Spanish under the radical teacher Teodoro Sandiko served as the first step in breaking down that bondage of silence and the customary acceptance of women’s inferiorization. Their spontaneous agitation may be conceived as their recognition of “necessity” as freedom when they reached out to the propagandists in Madrid and outside Malolos, a strategic move embodying the pedagogical principle of socializing what was deemed natural and historicizing what was deemed immutable, fated or predestined.

Ilustrado Hubris

In the letter, Rizal refined and complicated the analysis of the political economy underlying the Malolos women’s plight to a critique of the church-induced habitus (Bourdieu 1977) of submission and self-abnegation. The reason for this is that in the colonial setup, the ideological propaganda apparatus of the church and its capillary agencies predominated over any liberal or reformist tendencies of the unstable secular-civilian administration. His stress on individual resistance to authority distinguishes his concept of education as part of his essentially agonistic view of life conveyed to his nephew during his Dapitan exile:

To live is to be among humans and to be among humans is to struggle. But this struggle is not a brutal and material struggle with men alone; it is a struggle with them, with one’s self, with their passions and one’s own, with errors and preoccupations. It is an eternal struggle with a smile on the lips and tears in the heart. On this battlefield man has no better weapon than his intelligence, no other force but his heart. Sharpen, perfect, polish then your mind and fortify and educate your heart (1993, 375)

Self-discipline as Enlightenment desideratum was also what he was trying to articulate in the letter, except that he was more preoccupied with altering the psychophysical disposition of the Filipino women inured to passivity, obedience and silence, which over-determined the fates of Maria Clara, Juli and Sisa. This accounts for the stress on a militarized sense of corporate honor, a warrior ethos distinguished by an ascetic regimen in fulfillfing duty and obligations to the community, as if he was trying to convert the feminine habitus to a more competitive, adversarial mode (on the ethos of honor, see Ossowska 1970). It seems as though the entrepeneurial Rizal, who engaged in the abaca trade, complained of not earning enough as an eye-doctor, and played the lottery, was more preoccupied with inculcating the aristocratic virtues of the feudal nobility than the bourgeois ethos of regularity, thrift, and profit-calculating prudence. He was skipping the stage of hypocritical merchant capitalism (identified with a mercenary priesthood and parasitic native bureaucracy) in favor of a utopian meritocratic arrangement allowing the intelligent some elite privileges while maintaining a semblance of aristocratic decorum.

Although marginal to the plot of the Noli (in fact, the whole chapter “Elias and Salome” was excised from the final version), the character Salome displays more affinities with her Malolos sisters, given her relative control over her means of subsistence and her isolation. With Elias’ decision not to marry her in order to spare her the misery of a wretched family life, she plans to move to Mindoro and join her relatives. Living happily in the wilderness, desiring nothing but health to work, not envying the rich girls their wealth, Salome anticipates the nature deity Maria Makiling of Rizal’s reconstituted folklore, the patria of the exiled hero. Salome implores the fugitive Elias to live in her home: “It will make you remember me…When my thoughts go back to these shores, the memory of you and that of my home will present themselves together. Sleep here where I have slept and dreamed…it would be as if I myself were living with you, as if I were at your side” (Noli 216-17). The narrative conjures their togetherness, their marriage, their mutual belonging, in fantasy or compensatory wish-fulfillment that is invariably women’s mode of transcending their misfortune. What imbues space with sacramental import and historic significance is woman’s work, affection, care; hence Rizal’s extreme anguish that mothers perform their nurturing, child-rearing task well.

Envisioning the Totality

On December 31, 1891, shortly after completing the Fili, Rizal wrote to Blumentritt that the reformist La Solidaridad is no longer his battlefield but rather the Philippines (Zaide 1984, 213). His family had suffered an irreversible catastrophe when they were evicted by the Dominican friars from the Calamba hacienda the year before and his relatives persecuted. His sojourn in Hong Kong marks his definitive turn to a revolutionary solution for the colony; his epistolary political testaments dated 20 June 1892, and his founding of the Liga Filipina on his arrival in Manila in June-July 1892 herald the beginning of Sisa’s and Juli’s vengeance: all the victims of colonial tyranny are gathering for a coven/covenant to exorcise the demonic plague. Rizal’s own view of the integrative, pivotal years of his Dapitan exile may be discerned in the “structure of feeling” (Wiliams 1977) behind his statement to Fr. Pablo Pastells: “I am at present at the enactment of my own work and taking part in it” (1930-38, 63).

A more historicized appraisal of Rizal in this age of terrorism would thus move the center of inquiry to the Dapitan years following the Hong Kong interlude, the contacts with plebeian/proletarian strata interested in the Liga, and the Liga’s resonance (Olsen 2007). By exposing the limits of Simoun’s romantic idealism and Padre Florentino’s eschatological wish-fulfillment, we move to engage more with the Sisa-Salome nexus in the carnivalesque world of colonial Philippines deprived of any nomos or transcendental absolute authority. Rizal anticipates the postmodern predicament of the dissolution of a a meaningful world in vacuous finance-capitalism. Women’s vengeance against patriarchal nihilism lies submerged in Rizal’s communicative gesture to the Malolos contingent, potential cadres or partisans of the Katipunan-led revolution. This outreach mobilizes emergent and residual historical forces in a dialectical trajectory of canceling the negative (mystifying ideologies and practices) and salvaging the mother’s body/place. This itinerary of changes provides a seismographic index for elucidating Rizal’s radical critique, his theory of transforming patria and the regenerative delirium of its victims into a counterhegemonic historic bloc (Quibuyen 1999), the matrix of all subversive insurgencies.

We can sidetrack Simoun’s conspiracy in the Fili and focus instead on a utopian moment. In his annotations to Morga’s Sucesos, Rizal’s vindication of Filipino women’s honor (reiterated in the letter) finds eloquent testimony. It is a return to the past before mother-right was completely annulled, when the self-sustaining security of the gens (clan) had not completely yielded to the vulnerable, isolated nuclear monogamous family dominated by the property-owning male. Women still participated in socially necessary labor (Sisa’s horticultural knowledge is a survival) in the domestication of crops, before the complete dehumanization of mother-oriented communal ties in the subjugated colony. Because Filipina women are not a burden to the husband, she does not carry a dowry: “the husband does not take a heavy burden or the matrimonial yoke, but a companion to help him and to introduce thrift in the irregular life of a bachelor” (1999, 26). Even though the Filipina women before the Spanish conquest “represents a value for whose loss the possessor [parents] must be compensated, she was never a burden on her parents or husband; European families, however, seem to be in a hurry to get rid of their marriageable daughters, with mothers frequently playing a ridiculous role in the sale of her daughter. The sale and purchase of Filipino women is not a custom in the past, according to Rizal’s ethnological research:

The Tagalog wife is free and respected, she manages and contracts, almost always with the husband’s approval, who consults her about all his acts. She is the keeper of the money, she educates the children, half of whom belongs to her. She is not a Chinese woman or a Muslim slave who is bought sometimes from the parents, sometimes at the bazaar, in order to lock her up for the pleasure of the husband or master. She is not the European woman who marries, purchases the husband’s liberty, initiative, her true dominion being limited to reign over the salon, to entertain guests, and to sit at the right of her husband (1999, 26).

Allowing for a certain overstatement in the position of women in pre-colonial times, it is accurate to state that in the communal stage of the barangay, the division of socially necessary labor and with it, the specification of gender roles, has not yet been affected by commodity production and the circulation of exchange values. To the degree that women participate integrally in productive work, as well as with the reproductive labor of the household, they enjoy a measure of equality with men. As soon as private property (land, labor, commodities) becomes the dominant logic of the social order, male supremacy and monogamy prevail, supplemented by adultery and prostitution (Leacock 1972). When women were excluded from productive work and confined to kitchen and boudoir, their participation in political and public affairs also ended. With the male partner absent or emasculated, Sisa and Salome enjoyed a latitude of activity, a degree of autonomy, not shared by Maria Clara, Paulita Gomez, or Leonor Rivera.

We may hypothesize that this is one of the reasons why Rizal found Josephine Bracken, whom he celebrated in his “ultimo adios” as “dulce extranjera,” a breath of fresh air. It was a temporary respite from the surveillance of the traditional mother and his female siblings. Even though she was obedient, meek, and did not answer back when Rizal lectured, she belonged to the European/Western “race” and was not averse to engaging in manual labor in Dapitan. Clearly, Rizal was not threatened by her, as he was by Nelly Boustead, Gertrude Beckett or the business-minded Viennese temptress; she was an orphan, with “nobody else in the world but me [Rizal]” (1993, 417). In the hours before his death, Rizal wrote his family, asking forgiveness and requesting them to “Have pity on poor Josephine” (1993, 439). After her marriage to Rizal and his execution, Josephine Bracken actively participated in the revolutionary war led by General Emilio Aguinaldo (Ofilada 2003), perhaps realizing a fragment of Rizal’s image of those formidable Spartan mothers.

Intervention from the Mountain: A Millenarian Project?

Whatever the impasse of contradictions undermined his life, Rizal never gave up amor patria, the “most heroic and most sublime human sentiment,” He celebrated this obsessive nostalgia for the homeland in his first propagandist contribution to Diariong Tagalog (20 August 1982) when he landed in Barcelona on his first sojourn in Europe. Rizal is rhapsodic in proclaiming his adoration for the Motherland which inheres in every human: “She has been the universal cry of peace, of love, and of glory, because she is in the hearts and minds of all men, and like the light enclosed in limpid crystal, she goes forth in the form of the most intense splendor” (1962, 15). She is incarnate in fantasy, in the mythical figures associated with the natural surroundings, with the soil and rivers of the native land: “And how strange!” The poorer and more wretched she is, the more one is willing to suffer for her, the more she is adored, the more one finds pleasure in bearing up with her “(1962, 16). Geographical space, the occupied territory, becomes a concrete, lived place; it mutates into a libidinally charged locus of pleasure and self-sacrifice. When the motherland is in danger, the more intense the desire to come to her aid; the motherland symbolizes all those kin you have lost, the fountainhead of dreams, but also where “true Christianity” abides. Rizal finally identifies what he would later address, in his farewell poem, “mi patria idolatrada, dolor de mis dolores/Querida Filipinas,” with Christ “on the night of his sorrow.” Our sacrifices will revive the dying, suffering homeland (in the martyr’s allegorical rendering), now taking the persona of Josephine Bracken--“mi amiga, mi alegria”--now that of Maria Makiling and her enchanting metamorphosis.

It is instructive that Rizal, instead of dwelling on the didactic fable of Malakas and Maganda (coopted by the hired publicists of the Marcos dictatorship 1972-1986) born together as a sign of gender parity, calls our attention to the legend of Maria Makiling, the nature goddess. While inhabiting the borderline between nature and civilization, she remained a virgin, “simple and mysterious like the spirit of the mountain.” Initially, she favored humans with her grace and bountiful beauty; but when she was deceived by her lover, she took revenge. Rizal suggests that perhaps she was infuriated by the attempt of the Dominican friars “to strip her of her domains, appropriating half of the mountain” (1962, 107). The goddess scolded her human lover when he took another bride: “inasmuch as you had not courage either to face a hard lot to defend your liberty and make yourself independent in the bosom of these mountains; inasmuch as you have no confidence in me, I who would have protected you and your parents, go; I deliver you to your fate.” Since then, the goddess never again showed herself to humans, no matter how hard they searched for her “along the famous ascent that the friars called filibustera,” according to Rizal. The harmony of humans and the world is sundered by predatory acquisitiveness, by the exploitation of nature to produce subsistence, so “neither the enchanted palace nor the humble hut of Mariang Makiling could be glimpsed” (1962, 110).

And so did Salome abandon her home in the forest, so did Sisa and Juli depart from the fallen world of Padre Camorra, Padre Damaso and Padre Salvi, of Dona Consolacion, the alferez and guardia civiles—the outposts of the crumbling Spanish empire. In the 1892 Hong Kong letter, he declared: “I desire, furthermore, to let those who deny our patriotism see that we know how to die for our duty and for our convictions. What matters death if one dies for what is loved, for the country, and for the beings that are adored?” (Palma 1949, 351). Sisa’s vengeance arrives here with the martyr’s call to the Motherland to pray for “our unhappy mothers who in bitter sorrow cried,” rendering judgment on those condemned to languish in a world where slaves bow before the oppressor, where faith kills. Uncannily serendipitous, inhabiting the borderland between patriarchy and matrilineality, the surname “Rizal” is not found in the clan genealogy; it was given by an unnamed provincial governor to distinguish the Mercados of Calamba, a gratuitous addition which fulfilled in the ripeness of time its prophetic signification in designating “a field where wheat, cut while still green, sprouts again” (Guerrero 1969, 19).

REFERENCES

Aguilar, Delia. 1999. Toward a Nationalist Feminism. Quezon City: Giraffe.

Arcilla, Jose. 1991. Rizal and the Emergence of the Filipino Nation. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University

Baron-Fernandez, Jose. 1980. Jose Rizal: Filipino Doctor and Patriot. Quezon City: Manuel Morato.

Bourdiieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. London: Cambridge University Press.

Caudwell, Christopher. 1971. Studies and Further Studies in a Dying Culture. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Constantino, Renato. 1970. Dissent and Counter-Consciousness. Quezon City: Malaya Books, Inc.

Craig, Austin. 1913. Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal. Manila: Philippine Education Co.

Ebert, Teresa. 1996. Ludic Feminism and After. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1958. Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: Meridian Books.

Feria, Dolores. 1968. “The Insurrecta and the Colegiala.” In Rizal: Contrary Essays, ed. Petronilo Daroy and Dolores Feria. Quezon City: Guro Books.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1978. “From ‘In Search of the Educational Principle.” In Studies in Socialist Pedagogy. Ed. Theodor Mills Norton and Bertell Ollman. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Guerrero, Leon Maria. 1969. The First Filipino: A Biography of Jose Rizal. Manila: Vertex Press Inc.

Hays, H.R. 11958. From Ape to Angel. New York: Capricorn Books.

Joaquin, Nick. 1988. “Small Beer: Love Scene.” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Feb. 13): 11.

Kautsky, Karl. 1925. Foundations of Christianity. New York: International Publishers.

Kristeva, Julia. 1986. The Kristeva Reader. New York: Columbia University Press.

Leacock, Eleanor B. 1972. “Introduction.” Frederick Engel, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. New York: International Publishers.

Lopez, Salvador P. 1968. “Maria Clara—Paragon or Caricature?” In Rizal: Contrary Essays, ed. P. Daroy and D. Feria. Quezon City: Guro Books.

McLellan, David. 1970. Marx Before Marxism. New York: Harper and Row.

Majul, Cesar A. 1961. “On the Concept of National Community.” In International Congress on Rizal. Manila: Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission.

Nakpil, Carmen Guerrero. 1980. “The Filipino Woman.” Asian and Pacific Quarterly XII, 2 (Summer): 10-18. First printed in the Philippines Quarterly, 1952, and reprinted in Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, Woman Enough and Other Essays (Quezon City, 1973).

Ocampo, Ambeth. 1998. “Rizal’s Morga and Views of Philippine History.” Philippine Studies, 46.2 (1998): 184-214.

Ofilada, Macario. 2003. Errante Golondrina. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Oizerman, T. I. 1981. The Making of the Marxist Philosophy. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Olsen, Rosalinda N. 2007. “Rizal and the Myth of the Golden Pancake.” Bulatlat vii. 5 (March 4-10).

Ossowska, Maria. 1970. Social Determinants of Moral Ideas. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Palma, Rafael. 1949. The Pride of the Malay Race. New York: Prentice Hall.

Quibuyen, Floro. 1999. A Nation Aborted. Quezon City: Ateneo University Press.

Rizal, Jose. 1930-1938. “Rizal to Blumentritt, London, Nov. 8, 1888.” In Epistolario Rizalino. Vol V, Part 1. Ed. Teodoro M. Kalaw. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

----. 1950. The Young Rizal. Translated by Leon Ma. Guerrero. Manila: Bardavon Book Co.

----. 1964. Miscellaneous Writings of Dr. Jose Rizal. Vol. VIII. Manila: National Heroes Commission.

----. 1984. “To The Young Women of Malolos.” In Gregorio Zaide and Sonia Zaide,, Jose Rizal. Manila: National Bookstore.

----. 1993. Letters Between Rizal and Family Members 1876-1896. Manila: National Historical Institute.

----. 1999. Quotations from Rizal’s Writings. Translated by Encarnacion Alzona. Manila: National Historical Institute.

----. 2004. Noli Me Tangere. Translated by Soledad Lacson-Locsin. Manila,Philippines: Bookmark.

-----. 2004. El Filibusterismo. Translated by Soledad Lacson-Locsin. Manila, Philippines: Bookmark.

San Juan, E. 1999. Filipina Insurgency. Quezon City: Giraffe.

Thomson, George. 1955. The First Philosophers. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

----. 1968. Aeschylus and Athens. New York: Universal Library.

Tucker, Robert C. 1972. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: W.W. Norton.

Warner, Marina. 1976. Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary. New York: Vintage Books.

Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zaide, Gregorio and Sonia Zaide. 1984. Jose Rizal: Life, Works and Writings of a Genius, Writer, Scientist and National Hero. Manila: National Bookstore.

Zizek, Slavoj. 2008. Violence. New York: Picador.

[ Copyright © 2011 E. SAN JUAN, Jr. ]

-----ABOUT THE AUTHOR

E. SAN JUAN, Jr. was recently a fellow of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University. He is emeritus professor of English, Comparative Literature, and Ethnic Studies at several universities in the U.S.; he has also taught at Leuven University, Belgium; Tamkang University/National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan; Trento University, Italy; the University of the Philippines, and Ateneo de Manila University. Among his books are US IMPERIALISM AND REVOLUTION IN THE PHILIPPINES (Palgrave); IN THE WAKE OF TERROR (Lexington); BALIKBAYANG SINTA: AN E. SAN JUAN READER (Ateneo); FROM GLOBALIZATION TO NATIONAL LIBERATION (University of the Philippines), CRITIQUE AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION (Mellen), and CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS (Lambert LAP, Saarbrucken, Germany). He is preparing a collection of his recent poems in Filipino, with English translations, entitled MAHAL, MAGPAKAILANMAN.

ADDRESS: 117 Davis Road, Storrs, CT 06268, USA

Comments