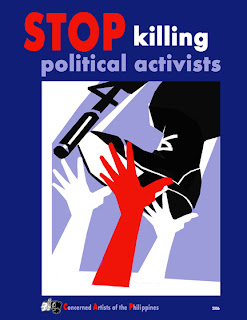

SMASH THE U.S.-ARROYO KILLING MACHINE!

THE MAY DAY THESES: EMERGENCY TOOLKIT FOR THE DISMANTLING OF THE ARROYO KILLING MACHINE

By E. SAN JUAN, Jr.

Philippine Forum, New York

Ang sagot sa dahas ay dahas din, kung bingi sa katwiran.

---JOSE RIZAL

No uprising is ever wasted. Each is a step in the right direction.

--SALUD ALGABRE, leader of the Sakdal Insurrection

Election day, May 14, 2007: a time of reckoning for the oppressors, a time of judgment for the avengers of the oppressed, exploited and slaughtered generations of Filipinos, from the 1.4 million killed by the U.S. invaders in the Filipino-American War (1899-1913) to the over 850 victims murdered by Arroyo and her generals and their death-squads. Even as more imbecilic pretexts and mendacities are spun by Arroyo apologists from the recent Burgos/Posa/Arado kidnapping, and the well-oiled cheating dynamos revving up for a last-ditch effort, synchronized with the rusty gears of the killing machines of the AFP/PNP, the masses are assembling for a final confrontation. Who will prevail? I rehearse the “Seven Theses,” published earlier in BULATLAT, on the possible answers to that urgent question, with some key revisions.

----------------------------------

A fortuitous conjuncture of recent events seems to augur the inexorable downfall of the Arroyo presidency. With the defiant manifesto of “Nanay Ude” (Lourdes Rubrico) of UMAGA (Ugnayan ng Maralita Para sa Gawa at Adhikain Federation) and the attempted killing of KARAPATAN officer Jose Ely Garchico and the abduction of Maria Luisa Posa-Dominado (SELDA) and Nilo Arado (BAYAN), we confront the desperate panic of the regime side by side with the implacable resistance of the popular forces. Oppression always begets resistance, as the adage goes. And with more oppression goes certain retribution.

The inertia of tyranny at first seemed impervious to humanitarian blandishment. Arroyo may shed crocodile tears, but her cabal of generals and security advisers doesn’t care and seems addicted to the opium of violence. Despite Alston’s exposure in the Human Rights Council of the “Order of Battle” blueprint of OPLAN BANTAY LAYA I and II, Arroyo’s minions continue to ratchet up the score of extra-judicial killings and forced disappearances. Despite the judgment of the Permanent People’s Tribunal and rigorous condemnation by Amnesty International, National Council of Churches of the Philippines, Asian Human Rights Commission, the Japanese Human Rights Now, and the InterParliamentary Union, among others, of the obscene platform of “impunity” for operatives linked to the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine National Police (PNP), the political murders show no signs of abating. In an unprecedented “overkill,”AFP troops have saturated urban poor communities in Metro Manila and elsewhere to openly harass and intimidate citizens inclined to BAYAN MUNA and other progressive party-list candidates in the weeks before the May elections. What more atrocities are being hatched in Malacanang in step with Bush’s global war of terror?

Before the May 14 elections, the Arroyo clique may be gearing to “clean up its act” by public-relations magic. In a belated response to the concerns of U.S. Senator Barbara Boxer, Rep. Ellen Tauscher, and the U.S. State Department officials over U.S. aid being used for the vilification and summary executions of activists, the Arroyo -AFP’s show of a “state of denial” can be gleaned from the bureaucratic maneuvers of creating so-called special courts to try human rights cases. This comes after Alston’s witnesses were killed, betraying the tendentious character of such reforms. Could this cover up or compensate for the utter insipidity of Task Force Usig and the Melo Commission? It would be wishful thinking to believe in a sudden reversal of entrenched policy.

Scourge of the People

Unless her U.S. sponsors demand more concrete measures to stop the killings, the Arroyo clique will cheat—as KONTRA DAYA and others have predicted based on plans already hatched with premeditated care—and cheat massively in the May elections. It is only proceeding with “business as usual,” in the time-honored tradition of elections since 1946. The regime will then quickly proceed to implement the Human Security Law that will finally legalize the “de facto martial law” which, for Senator Jamby Madrigal (speaking at the People’s Tribunal at The Hague in March), already prevails. But legitimacy cannot be earned by legislative fiat. Last April 18, the University of the Philippines University Council passed a resolution condemning Arroyo’s curtailment of civil liberties, a mild show of protest from a fraction of the salaried intelligentsia. However, that is still symptomatic of the fact that Arroyo lacks that essential element of hegemonic consensus needed for any ruling bloc to survive. Violence may soon become the only weapon available, a sign of total moral and political bankruptcy of that “elite democracy” so beloved by former “left-wing” friends who hailed “the democratic space” of Cory Aquino as she was about to massacre the Mendiola peasant protesters, a class penchant proved again in the Hacienda Luisita massacre of 16 November 2004.

Urgent questions interpose themselves between local and international developments. Amid unceasing U.S. political-military intervention, can the realization of martial law de jure be stopped? Can the killings and abductions be deterred if not halted? Can the national-democratic opposition initiate a wider, more in-depth realignment of all anti-imperialist forces throughout the country? Can we establish a more radical discursive and organizational framework to build the united front for nationwide insurrection, rallying the middle strata beyond what has already been accomplished so far?

As of now, BAYAN and BAYAN MUNA, the main progressive detachments, by themselves alone cannot mount a sustainable challenge to the terrorist Minotaur without either getting the support of other nonleftist anti-Arroyo forces, or neutralizing them. What other sectors can be mobilized to strengthen the democratic forces and unleash emancipatory energies that have been stifled by authoritarian habits and practices grounded in the comprador-feudal structures of our society? What historic openings for liberation might be seized from this coming electoral exercise that can precipitate immediate change? Or if not that, at least, catalyze a regrouping of forces that can ultimately prove pivotal not just for the collapse of the Arroyo regime but also for the continued growth of participatory democracy centered on worker-peasant protagonism? What theoretical and practical breakthroughs may be read from the signs of micropolitical resistance in the city and countryside, as well as in the turmoil of the recalcitrant Filipino diaspora worldwide?

Here we take cognizance of the economic and social facts already rehearsed in recent movement documents from the liberated zones, as well as numerous IBON analysis of the sharp polarization of social classes in the last six years. We need an armed people’s defense force, no doubt, to relieve the agony of ruthless AFP/PNP counterinsurgency drives. On another occasion, we hope to explore the problem of why the strategy of people’s war (as traditionally construed) predicated chiefly on military action deviates from the principle of class struggle as a political resolution of historic contradictions by a combination of diverse means/modes, not just by violent means. Any physical combat in the social realm is, as Clausewitz once observed, always an extension of politics by other means. Yes, “el pueblo unido seran jamas vencido.” But it is still a long way to go in uniting “el pueblo,” ridden as it is with sharp divisions across the multiple axes of gender, ethnicity, religion, locality, and other cultural/ideological determinants that underlie the structural class cleavage. The U.S.-imposed neocolonial “social contract” may show signs of unraveling; the point is not just to interpret but to hasten its complete breakdown.

We demur from the triumphalism of our comrades, notwithstanding the heroic advances that have already been registered in the ejection of U.S. bases in 1991 and the Subic Rape case in 2006 (to cite only two examples). The dogmatic hubris of vanguardism cannot let us forget the regression to militarism/urban adventurism committed by those who were targeted by the Second Rectification movement. Such left and right tendencies will always exist in a neocolony severely ravaged everyday by capitalist alienation, commodification, anomie, as well as the destructive effects of archaic, feudal practices (such as sexist-masculinist abuses, clientelism, religious skullduggery, etc.). Neither pessimism of reason nor optimism of the will can help, I think, but a consistent regimen of criticism-self-criticism of political calculation can assist us in learning from mistakes of the past and thus forge a less wasteful path of social transformation.

Realize the Impossible

We seek to broach here a more heuristic and self-reflexive line of cognitive mapping of the sociopolitical arena. We hope to advance the anti-imperialist struggle within the framework of what is feasible in the short-term compass of Arroyo’s moribund tenure. “Realize the impossible!” –this slogan rests on grasping what is possible, just as freedom rests on comprehending necessity. To be sure, the people’s cause of social justice and true independence will emerge victorious in the end, via an orchestration of all means of struggle attuned to the dynamic changes in the political consciousness of various sectors. Vanguardism cannot preempt the slow hard labor of mass political education, organizing, and critique. The basic question is: how can we move out of this morass of impunity and relative disarray of anti-Arroyo forces? After all, Crispin Beltran is still detained by the military, and Satur Ocampo (as well as others of the “BATASAN 6,” “TAGAYTAY 5,” and hundreds of activitists named in the AFP “Order of Battle” a copy of which was recently submitted by Alston to the UN Human Rights Council) still faces an uphill legal battle, and all anti-imperialist militants face threats of prison or “neutralization” every moment of the day.

Here we will concentrate on the specific contradictions faced by the ruling bloc and its ramifications. This positing of problems faced by the enemy is offered as a way of revitalizing the project of communal democracy so necessary to advance the national-democratic program as a stage of socialist reconstruction, within the framework of an uninterrupted revolutionary process. Of course, unpredictable events and new players/actors may intervene that could gradually, or by leaps and bounds, change the parallelogram of forces and require a new theoretical calibration of class trajectories. However, we need to always pursue the principle of historical-materialist analysis in order to unfold the inner laws of motion from the surface of everyday circumstances whose bizarre oscillation may seduce us into easy consolations and premature celebrations of victories. True, you need to break eggs to make an omelette; but there is no guarantee that the omelette will be edible or savory at all. The categorical imperative for the wretched of the earth is still: Makibaka, huwag matakot!

Needless to say, the propositional form of this intervention invites further scientific inquiry and practicable exchange, with the resulting hypotheses to be tried in concrete praxis in the historical arena. What is necessary is to agree on the purpose and goal of the national-democratic project of replacing the Arroyo regime, not only illegitimate but politically and ideologically bankrupt, with one reflecting the liberatory aspirations of the exploited classes and all sectors committed to egalitarian democracy and genuine national independence. Here the desideratum of “the mass line,” its ripeness, signifies everything.

Impeachment Feasibility

Thesis 1: After the Garci exposure and the failed impeachment attempts, the Arroyo bloc has definitively lost any shred of legitimacy it may have putatively enjoyed after People Power 2. While bribes and other inducements offered to Batasan trapos have practically made the impeachment route counterproductive, the educational-propaganda value of the impeachment case, as well as the obscenity of extrajudicial killings, has not been fully exhausted. Other venues have to be found. A preponderant number of Filipinos in the U.S., for example, doesn’t know the details, much less the implications, of the Garci fraud. Like other migrants, they still cling to the belief that the incumbent (like the Marcos regime in the seventies) should be allowed to run the government and preserve law and order for everyone.

The task then is to engage in a wide-ranging pedagogical, “conscientizing” effort of propagating the merits of the impeachment brief to as wide a constituency as possible, appealing to the traditional sense of fair play, clean elections, honesty, and so on. This will reach otherwise conservative, pro-US sectors of the population in the country and abroad, and also energize liberal fractions of the “national bourgeoisie” (now reduced to rentier and comprador pursuits). This is not to endorse parliamentary cretinism; rather, it is to maximize what is still legally allowed in a republican framework of class conflict and use it as a point of departure for accelerating political education and organizing toward insurrectionary readiness. This is to engage the bulk of civil society still adhering to the old maxim, Salus rei publicae suprema lex, bearing in mind that this current rei publicae exists to reproduce class inequality and imperialist domination.

Authoritarian Cul de Sac

Thesis 2: The nearly absolute reliance of the Arroyo clique on AFP/PNP counterinsurgency tactics, including extrajudicial killings and selective persecution (Beltran, Ocampo) of progressive dissenters, is a clear symptom of weakness due to the loss of suasive power. A militarized bureaucracy (entrenched since the Marcos period) has no political intelligence at all, tied to a technocratic ethos. Its tactics are reactive, hence their agents fall prey to conventional guerilla maneuvers even with the help of sophisticated techniques given by Pentagon/U.S. advisers. Without genuine popular support, the regime’s days are numbered.

Aside from private armies of thugs and assorted mercenaries, the main coercive agency of the ruling bloc is the U.S-trained and U.S.-indoctrinated military and police apparatus. Such limitation of agency cannot be remedied by more bribery of politicians, or by expedient compromises with other fractions of the oligarchy: the Marcoses, Joker Arroyo-type vacillating “libertarians,” etc. Arroyo and her Cabinet Oversight Committee on Internal Security, however, are bedeviled by three ineluctable determinants: 1) internal dissension within the military ranks due to the politicized nature of promotions, division of the loot, etc.; 2) limited internal resources, including decimation of ranks through desertion, casualties, intractable clandestine activities, etc.; and 3) utter dependence on the Pentagon and Washington for logistics, training, etc., which may suffer the vicissitudes of political shifts in the metropole. Aside from clientelism and opportunism, the military-police bureaucracy is riddled with vicious in-fighting and personality cults that cause inefficiency, paralysis, etc. Moreover, as in any uneven, dependent formation, there exist in the ranks honest elements who may be won over in the course of the struggle, hence the key lies in commonalities of political aims, not ideological standardization.

Balikbayans Blasting the Bastions

Thesis 3: A wholly new condition has emerged since the Marcos dictatorship: the phenomenal increase of OFWs (Overseas Filipino Workers). About three thousand leave everyday, a million every year, adding to the nearly 10 million Filipinos abroad. As already established, the temporary stability of the economy hinges on the ability to pay the foreign debt, which in turn depends on the continuing growth of remittance of dollars from OFWs, a large part of which comes from the Middle East and North America. Foreign investments have declined considerably, though transnational corporations can still exert some influence (as in the Walmart-Gap criticism of Arroyo policies handicapping union struggle for work-place rights). What is more valuable for the corrupt Establishment is the huge reservoir of taxes and fees extorted from OFWs through the OWWA Omnibus Policies amounting to at least P17 billion so far, which will surely be raided again for this May exercise. If the migrant community becomes fully mobilized in fighting for social, cultural and political rights, this can deliver the heaviest blows on the ability of the regime to deliver on its debts in time, satisfying the IMF/World Bank and the greedy appetite of finance capital.

Given the precarious nature of overseas hiring (consider recent Saudi Arabia’s restrictions, Taiwan’s prohibitions, etc.) tied to the geopolitical prospect of heightened conflicts in the Middle East, as well as periodic tremors in the Asian region (affecting Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong—the largest employers of OFWs), the Arroyo regime is vulnerable to such reverberations. Any explosion of conflict in those regions is bound to produce dire repercussions on the local political economy. This is where MIGRANTE and other formations oriented to OFW concerns are bound to play a key and possibly decisive role in precipitating a crisis of failure to pay both internal and external debts fatal to the ruling bloc.

Moros Undefeatable and Inescapable

Thesis 4: The Moro insurgency remains an integral part of our national-democratic struggle. The Moro people have suffered the most since the Marcos dictatorship: hundreds of thousands killed, with more than half of the four million internal refugees coming from the Moro villages and towns. They have also rallied the largest armed combatants in the country and inflicted severe blows on the AFP. The unrelenting resistance of the Moro community (represented currently by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and sections of the Moro National Liberation Front) cannot be assuaged, or fully pacified, by Arroyo’s diplomacy and cooptation. Nor can the AFP/PNP, even with the help of U.S. Special Forces, ever succeed in eliminating the Abu Sayyaf or the conditions that reproduce such a phenomenon. Not because the Abu Sayyaf is a parasitic and coeval creature of the CIA and its military/civilian patrons, which remains the case—Bush’s War on Terror subsists on the continuing existence of this bandit group—but because this is tied with the whole turbulent milieu of the Islamic world (Indonesia, Malaysia, parts of Thailand, Bangladesh, Pakistan, etc.) and the internal decay of its structures and ethos. Note that a large part of the combat-ready AFP troops are tied with the fighting in Mindanao and Sulu, thus enabling breathing space (exchanging space for time) for building up the liberated zones and pursuing a war of attrition and encirclement.

Here, the Organization of Islamic Conference is a crucial international body whose ideological shifts will certainly affect the capacity of Moro separatism to grow or diminish. What is imperative is for the radical assemblage to incorporate the Islamic resistance much more adequately than it has done so far. A wider anti-imperialist united front cannot be realized without the substantive participation of the Moro movement for autonomy. Luis Jalandoni’s affirmation of the Moro (and other national minorities’) right to self-determination, emphasized in his March 23 presentation to the Permanent People’s Tribunal, is a salutary move in the right direction.

Subterranean Rumblings

Thesis 5: Aside from the Bangsa Moro people, the indigenous communities (Lumads, Igorots, etc.) need special inducements for their inclusion in the united front against the Arroyo clique. So far, this has not been done, despite advances in the Cordillera front. We need to pay closer attention to indigenous practices of solidarity and coalitional work, esp. in the mines, remote villages, and plantations. Perhaps the nationalist appeal for liberation needs to be modified to promote the local demands for livelihood, preservation of ancestral lands, and fostering of local religious customs, including prophetic millenarianism. The same goes for the utopian experiments of artists, anarchists, and other marginalized sectors. Christian chauvinism remains the main obstacle here as well as dogmatic scientism and other “orientalist” prejudices. Can our postmodern babaylans stir up the slumbering chthonic energies of Mother Filipinas?

Arming the Spirit

Thesis 6: The religious front requires special analysis in the light of unrelenting U.S.-influenced evangelization. While the theology of liberation may have been eclipsed by actual practices of progressive “fundamentalist” sects, this aspect of the underground movement during the Marcos era may still be reconfigured to draw quietistic and conservative believers to a more dynamic worldly thrust that will dovetail with emergent programs of industrialization, sustainable development, and the building of a self-reliant economy. Given the attacks on the Philippine Independent Church, and reformist church officials of the Protestant denominations, there exist great opportunities to channel anti-statist sentiments in a more decolonizing political direction. This has been done with women, gays, and unorthodox intellectuals with their utopian dreams, so why can we not appeal to the salvific impulse and direct it to secular ends (material well-being, health, care for the environment)? Father Ed de la Torre’s incarnational politics awaits vindication in a revitalized theology of national liberation disabused of pettybourgeois reformist illusions. We need to call on the Jacobin spirits of Reverend Aglipay and Isabelo de los Reyes to aid us in this new materialist “reformation.”

Pedagogical Reconaissance Force

Thesis 7: Now that KABATAAN party, with its techno-cyber élan worldwide, has been launched, it may be superfluous to emphasize the imperative of arousing and cultivating the youth sector of the united front. Instead of accenting the age/generational aspect, we would rather stress the institutional category of students (from grade school up) that should be the target for intense conscientization and mobilization. After all, institutions, not status or age groups, serve as the sites of radical social transformation, the transmission belts of what Spinoza calls deus sive natura. As our history has demonstrated without fail, from the time of Emilio Jacinto and the Propagandistas to the First Quarter Storm of Ed Jopson, Judy Taguiwalo and Carol Pagaduan-Araullo, the institutional site of schooling/studentry functions as the crucial arena for political education, organization and agitation. Time, energy and resources should be allocated carefully and chanelled to this front in order to deepen, widen and reinforce the ground already sedimented by the pioneering initiatives of the League of Filipino Students (LFS), CONTEND, ACT, and other affinal assemblages. Students, not youth (to modify Rizal’s invocation), is the genuine hope of the motherland.

Imperial Rescue?

There is no doubt that the public support of the United States is probably the only driftwood the Arroyo bloc still clings to. But there is no certainty in permanent U.S. patronage that is always based on the prior claims of U.S. racial “manifest destiny,” that is, global hegemony. What is bound to snap the U.S-Arroyo linkage is this: Arroyo cannot pacify the internecine fighting of oligarchic factions, which may push Washington to opt for a substitute among the contending elite politicians. A carnage-prone state that cannot reconcile the internal feuds within elite ranks, much less conciliate the dispossessed, cannot defeat the popular challenge.

Fellow-travellers during the Marcos dictatorship failed to predict the dispensability of the dictator for the U.S., thus withdrawing from the electoral struggle in 1986. As the case of the Subic rapist Daniel Smith has recently shown, the U.S. always tests any administration in the crucible of subservience, whether by bribes (more military aid) or coercive pronouncements (suspension of the Balikatan exercises). And no group of subaltern functionaries is indispensable, as withdrawal of support for the Marcos dictatorship has shown if what is at stake is the preservation of the subordinate social relations of capital accumulation and its governability. If Arroyo proves totally discredited, and the impasse of her corrupt, fraudulent rule jeopardizes U.S. control and precipitates the entry of the National Democratic Front into the scene, then the U.S. will immediately abandon Arroyo and substitute the next compromise elite fraction. Thus the fight against U.S. political and military intervention remains central to the articulation of all the demands and goals of the national-democratic assemblage.

In sum, the U.S.-Arroyo terrorist state is plagued with incoherence, vulnerabilities, and intrinsic inadequacies characteristic of the authoritarian state in the periphery (an earlier treatise on this, Clive Thomas, The Rise of the Authoritarian State in Peripheral Societies, 1984, may be useful; obviously, the “global war on terror” and U.S. unilateral hegemonism have changed the historical context, thus the need for new analysis). The Arroyo state is neither a populist nor a classically fascist (European) state. It has neither vast popular cross-class support nor does it promote a messianic leader to channel middle-class frustrations, a racialized savior who promises redemption, or even to make “the nation great again” (as Marcos tried to do with the help of shoddy pundits like Blas Ople and other hirelings). Its use of violence is narrowly instrumentalist, not mystical or primordialist. (The old debate among Ernesto Laclau, Ralph Miliband, and Nicos Poulantzas on facism and populism in the European and Latin American context may be instructive here.) Of course, even if the Arroyo regime is saddled with multiple problems sketched earlier, it will not fall by itself (barbarism exceeding yesterday’s carnage is always an option)—the popular forces have to dismantle it gradually, or by leaps and bounds.

Point of No Return

This May election may prove to be a decisive turning point both for Arroyo and the anti-imperialist united front. It will certainly narrow the paths open to all contending forces. Either Arroyo will cheat and entrench her authoritarian rule, or the popular resistance will unseat her in a series of flanking moves and direct confrontations hitherto unforeseen. We are in that interregnum where the people can no longer accept the status quo and the ruling elite can no longer implement phony democracy in the old style—an in-between phase of the struggle replete with morbid symptoms; hence, either the old system crumbles, or its agonizing death-pangs are prolonged at the expense of the intolerable suffering of millions from globalized market profiteers and their local henchmen.

Let us repeat what seems to be commonplace now, though inflected in a more dialectical stance. Arroyo’s makeshift combination of trapos and militarists, Cold War ideologues, and pettybourgeois propagandists, betokens an expedient mechanism for narrow get-rich-quick schemes by manipulation of the State apparatus and raiding the public treasury. Except for its disproportionate use of the military and police in extrajudicial killings, regional counterinsurgency drives, massacres and tortures, the Arroyo state is a conjunctural result of several intertwined contingencies: electoral fraud, advanced disintegration of the oligarchic bloc of comparators-landlords-bureaucrat capitalists (their productive base has considerably diminished and their ideological control over peasants and workers has been countered by increased underground agitation and labor-union organizing); and, sad to say, the still divided mass of workers, peasants and middle elements who have not yet been effectively interpellated and fused into a revolutionary counterhegemonic bloc. In short, the objective conditions have ripened, but the subjective forces have not yet fully matured to take over state power, or articulate a new consensus, a new “common sense.” The alibi or escape route of OFWs still beckons. Nonetheless, the process of maturation can occur rapidly, depending on a sudden turn of circumstances that cannot be predicted despite our claim to know “the laws of motion” of the capitalist mode of production.

Our neocolonial condition has always been a permanent state of emergency. But it is not one imposed by Proclamation 1017, but by the vicious operation of sustained colonial oppression and imperialist havoc. The treason of the technocrats that Alejandro Lichauco (see his Hunger, Corruption and Betrayal, 2005) bewails is only a symptom of the general crisis of a minor neocolony that has been sharpening since 1946. No doubt, mass hunger has worsened. But everyone knows that poverty and suffering do not translate automatically into a fight for justice and equality. There are 25 million hungry Filipinos (roughly 3.4 million households) who are desperately hungry, but not all are marching for food and the overthrow of the iniquitous order.

Customary traditional beliefs, together with subaltern mentalities and habits, offer outlets of anger and grief; emigration and charity drives another. In After Postcolonialism: Remappping Philippines-United States Confrontations (Rowman 2000) and also in U.S. Imperialism and Revolution in the Philipppines (Palgrave 2007), I tried to analyze the institutionalized ideological mechanisms that perpetuate subalternity. No appeal to neoliberal “free market fundamentalism,” nor pluralist governance (how can the Batasan or the courts perform check-and-balance procedures when a culture of corruption and opportunism prevails?) will enable the reform of COMELEC, the trial of Gen. Jovito Palparan and his ilk, or the successful investigation of corruption and electoral fraud by the courts or Ombudsman of the current regime. Arroyo, however, cannot institutionalize anxiety and fear for a classic fascist mobilization since she has no genuine mass movement to deploy. Nor is there any affective identification with a leader who can channel persecutory anxiety against “communists fronts” (as Franz Neumann noted in The Democratic and the Authoritarian State, 1964). Her gambit hinges on the passivity of an electorate that can, however, be volatilized and reoriented by critical popular interventions in a revolutionary direction.

The Messiah Intervenes

Only two final points can be made here due to space limitations. As an emergency measure to undercut the “climate of impunity,” a tactical move of armed self-defense by local communities may be adopted. This can be done through exemplary arrest, trial and punishment of publicly known assassins, torturers, and abusive police and military officers. People’s justice needs no special juridical or moral justification. We don’t have to wait for these criminals to leave the country and be put on trial years from now in a European State which recognizes the International Court of Justice. We need only invoke the provisions of the CARHRIHL (the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law) that the Philippine government signed together with the National Democratic Front, which in turn draws its force from the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights and other ratified international laws. The question is: who has the power to implement it now? Time will tell.

A nagging question pursues us entailed by the last query. If, as has been repeated everywhere, the regime is irretrievably bankrupt and totally devoid of legitimacy, ruling only through force, deception and bribery, sustained only by the inertia of habit and the customary deference (the fabled “compassion” of the mythical Filipino) of the neocolonized subaltern, what needs to be done to finally bury it? Aside from the arguments drafted here, only an allegorical answer can be ventured here, since the concrete strategy is already being fleshed in the collective praxis of “the mass line”: The Messiah will come when you least expect it, and only through that tiny space of our prison’s emergency door about to be slammed shut. “For every second of time [is] the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter” (Walter Benjamin). It is the tiger’s leap into the presence of the Now blasted from the continuum of history. And “Messiah” is nothing but the nom de guerre of the combative people’s empowering agency, ang bayang lumalaban.

Prelude to Resurrection Day

Celebrating the Peoples Tribunal’s “guilty” verdict against the U.S.-Arroyo collusion, Mrs. Evangeline Hernandez, the mother of Benjaline Hernandez, one of the 850 victims of extrajudicial killings under the Arroyo dispensation (372 of them belong to activist or progressive sectors), announced in a public rally last March 27: “We who have lost our loved ones, who have been violated, will not allow Arroyo to prolong her stay in Malacanang…. The Filipino people will make this government pay for its blood debt.”

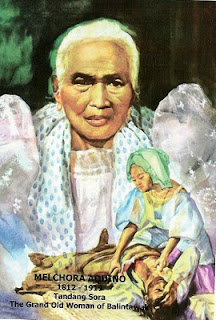

This cry of people’s justice will also signal the advent of a proactive grass-roots initiative that will begin to Filipinize the so-called “Maoist” insurgency that the U.S. State Dept. exploits to stigmatize the insurgency as “terrorist. Why “Maoist” when People’s China has long become thoroughly capitalist? Notwithstanding the now jejune RA-RJ squabble, why indeed can we not move beyond parroting the “Red Book” and invent our own national-liberation philosophy and methodology from the raw materials provided by our own rich history of anticolonial revolts combined with the world treasury of liberatory ideas (from the European Enlightenment that Rizal, Bonifacio, Mabini up to Amado V. Hernandez and Renato Constantino have incorporated in their praxis)? We have a massive durable history of revolutionary experiences, from Soliman to the Katipunan, the Hukbalahap, the First Quarter Storm, the generation of Maria Lorena Barros, the Tagamolila brothers, Lean Alejandro, and the present legal and extra-legal resistance.

In the wake of past defeats of peasant and worker revolts—nothing is really lost, as Salud Algabre reminds us, the indigenous culture of Filipino nationalism constantly renews its redemptive emancipatory voice by mobilizing new forces (women, church workers, ethnic minorities, gays, etc.) and utilizing all means possible in an all-encompassing radical democratic movement of all the oppressed and exploited millions. This struggle is organically embedded in local and regional social movements whose origin recalls the fight for national sovereignty and social justice in the tradition of third-world struggles (Gandhi, Ho Chi Minh, Che Guevara, Fanon, etc.), but are in practice identical with the local insurgencies of diverse communities against continued U.S. domination.

The Philippines, prosperous and sovereign, is still a project in the making. Our nation may be conceived as an “imagined” and actually lived/experienced ensemble of communities and civic formations—not just families or clans, but desiring-machines producing and reproducing the paramount Desire called Becoming-Filipino. Filipinas/Pilipinas, universal and singular, is in the process of being constructed and nourished through the many-faceted social and political resistance of Filipinos everywhere, in the homeland and abroad, against predatory corporate globalization and its brutalizing commodity-fetishism.

The embodied spirit of the nation, its ecumenical body germinal in the progressive groups and in the thousands of martyrs of the national liberation struggle, is creatively fashioning an appropriate culture of subversion, humanist solidarity, and self-empowerment worthy of its own people’s history, its collective vision and sacrifices, for freedom, material well-being, and human dignity.

Becoming-Filipino, an invincible power born from the ruins of the terrorist U.S.-Arroyo State--- Mabuhay ang sambayanang lumalaban! --###

___________

E. SAN JUAN works with Philippine Forum, New York City, and the Philippines Cultural Studies Center in Connecticut. He was previously Fulbright professor of American Studies at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, visiting professor of cultural studies at National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, and fellow of the Rockefeller Foundation Study Center at Bellagio, Italy. His recent books are IN THE WAKE OF TERROR (Lexington Books), FILIPINOS EVERYWHERE (Ibon), and U.S. IMPERIALISM AND REVOLUTION IN THE PHILIPPINES (Palgrave Macmillan).

Comments