FILIPINA INSURGENCY

Foreword to

FILIPINA INSURGENCY (Quezon City: Giraffe Books, 1999)

By E. San Juan, Jr.

No uprising fails. Each one is a step in the right direction.

--Salud Algabre

Faithful to the injunction “Always historicize!” I would like to situate the individual essays collected here in the conjunctural “thickness” of their origins.

Sometime in the mid-seventies, I edited Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win, the monthly newsletter of the Philippines Research Center (an affiliate of the anti-martial law groups in the United States), which featured in one issue the vicissitudes of the women's liberation movement in the Philippines. One reader asked why I wasted one issue on such a partial and minor trend; my somewhat protracted response took the form of an essay on socialist feminism, its background and prospect. This later evolved into chapter 8 of my book Crisis in the Philippines (South Hadley, Mass: Bergin & Garvey, 1986), included here as chapter 5.

As the historical record shows, the women's movement in our society has proved itself to be the most crucial and pivotal sector of the national-democratic struggle for genuine independence and people's empowerment. This is true mainly for most "third world" formations. The most succinct answer I can give now to the skeptical query is that without the goal of women's liberation from patriarchal, class, and racial oppression, any project of human emancipation is flawed. All social determinations involve gender and sexuality articulated with other categories. Likewise, all attempts at radical democratic transformation require grappling with the problem of gender inequality in theory and practice. Production in society (exploitation of surplus labor) where capital oppresses labor (both men and women) cannot serve as the all-encompassing paradigm that will subsume male exploitation of women in the domestic and reproductive spheres. The power relations between the genders commands an analytic specificity not reducible to class or any other categorical formulations. We might even propose, as a rhetorical trope to enunciate that thesis: Not only do women hold up half of the sky, as the old saying goes; they also make possible our standing on good old mother earth.

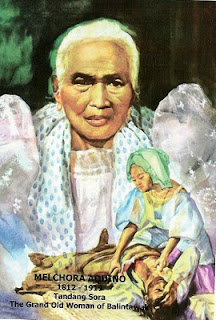

Over two decades have now passed since our heroic endeavor of building solidarity here and worldwide for the resistance against the U.S.-Marcos dictatorship. Most of the writings here were composed in the turbulence of the debates on cultural praxis during times of emergency. Long before the founding of MAKIBAKA, the first revolutionary organization of women, in 1971 under the leadership of Maria Lorena Barros, I wrote an introduction to the narrative (once attributed to Father Jose Burgos), La Loba Negra (Quezon City: Malaya Books, 1970), which forms chapter 1 of this book. The female protagonist of this fable harks back to such legendary heroines as Princesa Urduja and Gabriela Silang whose combative spirits will always haunt the "fathers" of the comprador nation-state. The historian Teodoro Agoncillo and Father Hilario Lim, both exemplary nationalists, requested my help in the struggle against sectarian, obscurantist forces then resurgent in the wake of Senator Claro Recto's crusade against U.S. aggression.

While this ingenious allegory centers on personal revenge (inspired no doubt by the ethics of Rizal's El Filibusterismo), the "cunning of history" unfolds the entanglement of the personal with the political, making the attack on patriarchy coincide with the battle against colonial abuse and racial tyranny. De te fabula. The feminist motivation, however, dissolved into the universal quest for justice. My thinking then was heavily influenced by a Hegelian Marxism derived from Georg Lukacs whose essays in English translation {entitled Marxism and Human Liberation published by Dell] I edited in 1972. It was only much later that I would discover Engels' The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, whose insights can provide the most valid framework for understanding women's revolt in such circumstances.

The second chapter on Nick Joaquin is taken from my 1988 book, Subversions of Desire: Prolegomena to Nick Joaquin (Quezon City: Ateneo University Press). It focuses on the patriarchal obsession with the threat of "the woman." There is no question that Joaquin's problematic is the complete antithesis to feminist principles. But I would like to stress that one should not mistake the author's explicit ideology with that of the text and its production of a sexual politics whose effects may contradict its putative origin.1 In short, one should not forget the tortuous dialectic between "base" and "superstructure," if one still wants to use those misleading, antiquated metaphors. My argument here is precisely to deconstruct such orthodox fallacies and propose that an oppositional praxis of reading can rescue elements in Joaquin's texts that can be useful in a liberatory strategy of critiquing patriarchal domination. Or else we succumb to the radical-feminist error of essentializing gender into biology or metaphysics.

We have of course many distinguished women writers like Genoveva Edroza Matute, Estrella Alfon, Rozario Guzman Lingat, Lualhati Bautista, and many others, whose singular achievements surpass Joaquin's or Villa's. They do not suffer for lack of attention and well-deserved esteem. In the future I hope to devote time and energy to the appraisal of women's writing in the Philippines; meanwhile, I am offering the essay on Jessica Hagedorn (presented in absentia at a conference in UCLA last May 1997) as an attempt to explore the predicament of Filipinos in the United States as felt or experienced by a Filipina who came of age in the sixties and seventies in California and New York City.2

Hagedorn's milieu may be distant in space from Joaquin's, but both are crisscrossed and contaminated by the traumatic years of the Marcos dictatorship and its rampant exploitation of women and children. Both attest to the persistence of sexist imperialism whose condition of possibility is partly the failure of the progressive forces to incorporate the fact of male supremacy/patriarchal power as relatively autonomous forces in the political economy of social transformation.3 Events have now fully substantiated this argument. The emergence of the Overseas Contract Worker (OCW) is testimony to the rise of the "woman question" as the fundamental and central issue in the quest for national liberation and popular empowerment.

My essay on the libidinal rhetoric and motivation in narratives of OCWs (to be published in a forthcoming issue of Lila, the journal of the Institute of Women's Studies, St. Scholastica College) betokens the centrality of women not only as producers but also as consumers in the globalized arena of late capitalism. The volume Filipino Women Migrant Workers: At the Crossroads and Beyond Beijing, edited by Ruby Beltran and Gloria Rodriguez (Quezon City: Giraffe Books, 1996) demonstrates this fact. Women OCWs not only hold up half of the sky; they sustain the iniquitous masculinist system with their remittances (the largest source of foreign exchange) without which the economy would collapse.4 The problem of women migrant workers, in my view, condenses in one life-form the most urgent contradictions of class, gender, race and nationality in our country today. Not only gender and sexuality as social constructions but also the changing constellation of power in the family is implicated in the lives of OCWs. Without confronting the reality of rape and physical violence against women (Flor Contemplacion and Sarah Balabagan represent thousands of Filipinas victimized by capitalist patriarchy around the world), we cannot move forward in our struggle for national autonomy, dignity, and efficacious sovereignty.

Despite setbacks in the progressive movement and opportunist betrayals by careerist intellectuals (what crisis doesn’t generate such ironies and reversals?), I like to think that we have advanced substantively in the process of eroding patriarchal authority. We can do better, of course, and storm the ramparts ahead of schedule. But history never proceeds in a straight line; one step forward, two steps backwards…. Everything is pregnant with its contrary.

Meanwhile it might be salutary to urge at this moment a renewed collective commitment to the ideal of “becoming woman” as a pedagogical rehearsal of what we anticipate. As the Canadian cultural critic Brian Massumi puts it: “Becoming-woman involves carrying the indeterminacy, movement, and paradox of the female stereotype past the point at which it is recuperable by the socius as it presently functions, over the limit beyond which lack of definition becomes the positive power to select a trajectory (the leap from the realm of possibility into the virtual—breaking away).”5

We need a cultural praxis and politics founded on a historical-materialist consciousness and utopian vision to forge ahead. This requires upholding the equality of women as a cardinal principle. In her excellent The Political Economy of Gender (1992), Elizabeth Eviota elucidated the "sexual division of labor" that traversed our history from the time of Spanish colonialism up to the colonial/neocolonial period under the United States. (The analogous history of Cuba has led during this socialist transition to the passage of the 1976 Family Code to rectify that sexual division of labor with mixed results.)6 Such a sexual division is always accompanied by the political conscientization and mobilization of women, an integral part of the emergence of Filipinos as a world-historical people.

In the summer of 1988, the editors of the U.S. publication Breakthrough (Spring 1989, pp. 22-32) interviewed a leading member of MAKIBAKA, the underground women's organization in the National Democratic Front, who reiterated that the advance of the liberation of women in the Philippines can only be achieved "by advancing the national liberation struggle at the same time." In effect, the ends of national, class and gender struggles are indivisible. Given the uneven development of the whole society, however, I would argue (as I do in the last chapter) that the historical specificity of women's oppression and women's resistance cannot be acknowledged by token gestures and thus discounted by simply reiterating the doctrine of the "basic classes" or the primacy of class over gender. I fully endorse Victoria Justiniani's assertion that the Filipina women's movement, while being part of the national struggle, has its own logic and singular aim: "to challenge patriarchy." 7 The essays collected here are intended to contribute to accomplishing that paramount feminist project.

NOTES

------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 See, for example, Cora Kaplan's instructive critique of Kate Millet's Sexual Politics in Feminist Literary Criticism, edited by Mary Eagleton (London: Longman, 1991): 157-70.

2 I direct readers to my other books for comments on related issues: The Philippine Temptation (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996) and Hegemony and Strategies of Transgression (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995).

3 The most forceful arguments so far on the failure of orthodox Marxism to take into account the historical specificity of male/patriarchal domination are the essays found in Women and Revolution edited by Lydia Sargent (Boston: South End Press, 1981), in particular the contribution by Heidi Hartmann entitled "The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism." See also Michele Barrett, Women;s Oppression Today (London: Verso, 1980). Lest some object to the ethnic/racial status of the women involved, I suggest women of color like Angela Davis--see her"Women and Capitalism: Dialectics of Oppression and Liberation" in Marxism, Revolution, and Peace (Amsterdam: B.R. Gruner, 1977): 139-71--and Martha Gimenez, "The Production of Divisions: Gender Struggles under Capitalism," in Marxism in the Postmodern Age, edited by Antonio Callari et al (New York: The Guilford Press, 1995): 256-65.

4 See Delia D. Aguilar, “Behind the Prosperous Facades,” Against the Current (March/April 1997): 17-20.

5 Brian Massumi, A User’s Guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1992): 87.

6 See Margaret Randall, Women in Cuba: Twenty Years Later (New York: Smyrna Press, 1981).

7 Delia D. Aguilar, "Engendering the Philippine Revolution: An Interview with Vicvic," Monthly Review (September 1993): 27. See also Delia D. Aguilar, "Gender, Nation, Colonialism: Lessons from the Philippines," forthcoming in Women, Gender and Development, edited by Lynn Duggan et al (London: Zed Books, 1995). See also Delia D. Aguilar, Toward a Nationalist Feminism (Quezon City: Giraffe Press, 1998) and Delia D. Aguilar and Anne Lacsamana, eds., Women and Globalization (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2004). My latest contribution to this field is found in Chapter 7 of Working Through the Contradictions: From Cultural Theory to Cultural Practice (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2004).

________________________________________

HABANG TINATALUNTON ANG MGA YAPAK NI KASAMANG SALUD ALGABRE

Alingawngaw ng tinig

“…walanginsureksiyong nasayang bawat isa’y

hakbang sa mahabang lakaran

patungong kalayaan….”

Bumubulwak ang bugso ng pananabik

sa darating na pagtitipan

Di natuloy sa pagtalunton

Kinaladkad nila ang ginahasa’t niluray na katawan

ng babaeng

pulang mandirigma

pinagbubugbog tinadtad ng bala

nakatimbuwang tila naghihintay

sa gilid ng bangin tagpuan ng mga darating

kinaladkad sa bukana ng batis na bumubulong

sa nabuksang pusod ng gubat

tadhanang bumulwak at umaalingawngaw

“iyong tinutunghay ano’t natitiis”

Sa pagitan ng naudlot na bangkay at hiyaw ng pananabik

--isang hakbang na lamang,

Ka Salud, pagbubuksan din—bumabangon

ang kinaladkad na halimuyak

bumubulwak sa bawat sugat

namumukadkad sa duguang labi

habang tinatalunton ang nasawing landas

itinadhanang halik na sumasalubong

bulalaslas ng pagbati sa kinabukasan

_________________________________________

E. SAN JUAN is co-director of the Board of Philippine Forum, New York City, and heads the Philippine Cultural Studies Center in Connecticut, USA He was recently visiting professor of literature and cultural studies at the National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, and professor of American Studies at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. Among his recent books are BEYOND POSTCOLONIAL THEORY (Palgrave), RACISM AND CULTURAL STUDIES (Duke University Press), and WORKING THROUGH THE CONTRADICTIONS (Bucknell University Press). Two books in Filipino were launched last July 2004: HIMAGSIK (De La Salle University Press) and TINIK SA KALULUWA (Anvil).

Comments